Jules Xavier

Shilo Stag

A veteran of the Battle of Vimy Ridge 106 years ago left his descendants a treasure trove of black and white photographs and memories he kept in scrapbooks.

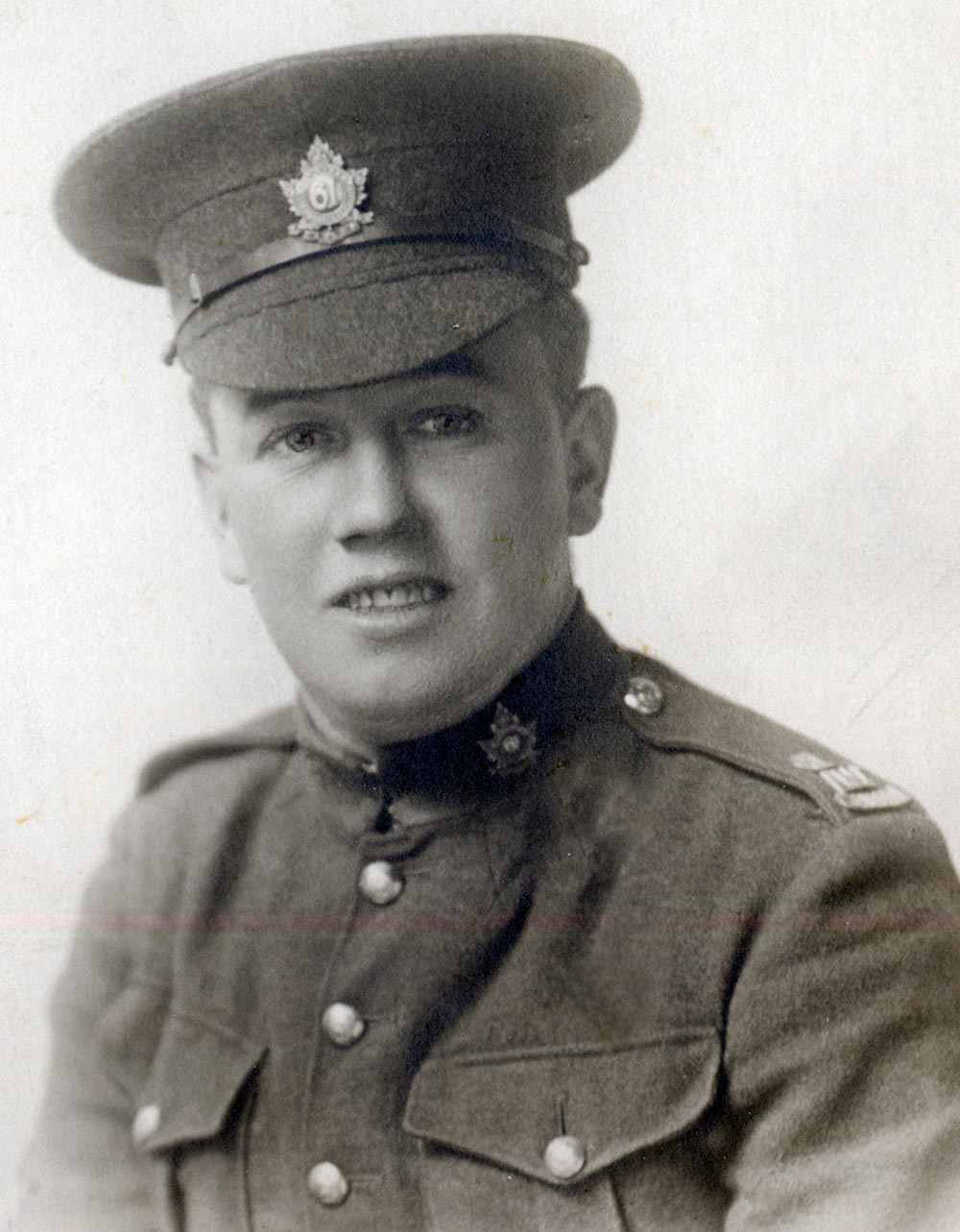

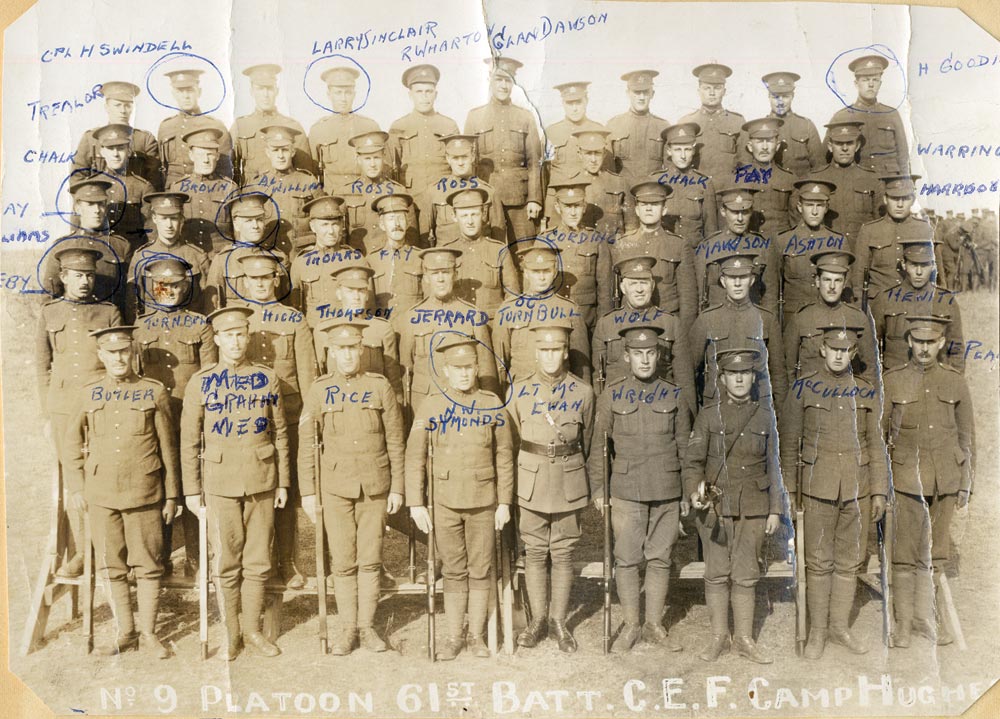

Using his trusty Kodak film camera, Bill May captured images at the now defunct Camp Hughes when it was a hive of activity as Canadian soldiers trained on the prairies before heading overseas as members of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) during the Great War.

Each photograph tells a story as best Pte May could compose with the camera equipment of that era. Once printed — usually in a postcard format where you could mail it after writing on the back, and placing a two cent stamp featuring King George V on it — he added to his First World War scrapbook.

One book called One Man’s Memories of WWI, May left remarks or identification of individuals he served with alongside the photo, or on the back.

The scrapbooks also include postcards he sent home to the family farm in Millwood — the words scrawled usually in pencil, but sometimes black ink — which soldiers could purchase at Camp Hughes. These cards were taken by photographers working with Advance Fotos out of Winnipeg, or at the time Camp Sewell, before it was renamed after MGen Sir Sam Hughes.

As you turn Pte May’s scrapbook pages it’s like going back in time as you look into the faces of soldiers long gone, whether they died on the battlefields of Belgium or France, or returned home to raise a family and die as grandfathers on Canadian soil.

Like Pte May, who died on Aug. 8, 1974 in Binscarth where he retired after leaving his final job at CFB Shilo, starting here when it was known as Camp Shilo. He was 82.

“He was meticulous in how he kept his scrapbooks,” offered granddaughter Kathleen Mowbray (nee Schrot) of Minnedosa. “[Aunt] Margaret [in Nova Scotia] has held on to a lot of the scrapbooks, and photos, from her dad, and we’re now starting to share them with other family members.”

Brother Kelvin Schrot of Sprucewoods thought it would be nice to share his grandfather’s story with the award-winning Shilo Stag to coincide with another anniversary of the Battle of Vimy Ridge.

“I’ve learned things about my family I did not know since [the Stag] started looking at my grandfather’s life, from being in the Army to working on this Base for all those years,” he said.

Born on April 8, 1892 in London, England to a family of eight brothers and a sister, Bill May was one of the first employees hired at Camp Shilo by the YMCA in 1940.

With his brother Harold, they arrived in Manitoba after their journey across the Atlantic Ocean brought them to Canada. With the First World War underway overseas, Pte May first married Grace Murdoch and started a family.

Brother Harold enlisted first, with the Winnipeg Rifles, and began training at Camp Sewell. In a postcard letter sent to his brother written on July 23, 1915, he wrote: “You got the [address] all right, but you did not put ‘Man’ on it and it went way down to Montreal. What do you think of the picture taken outside the tent?”

The postcard shows seven soldiers, including Harold, standing in front of military-issued blankets on the ground outside of their tent.

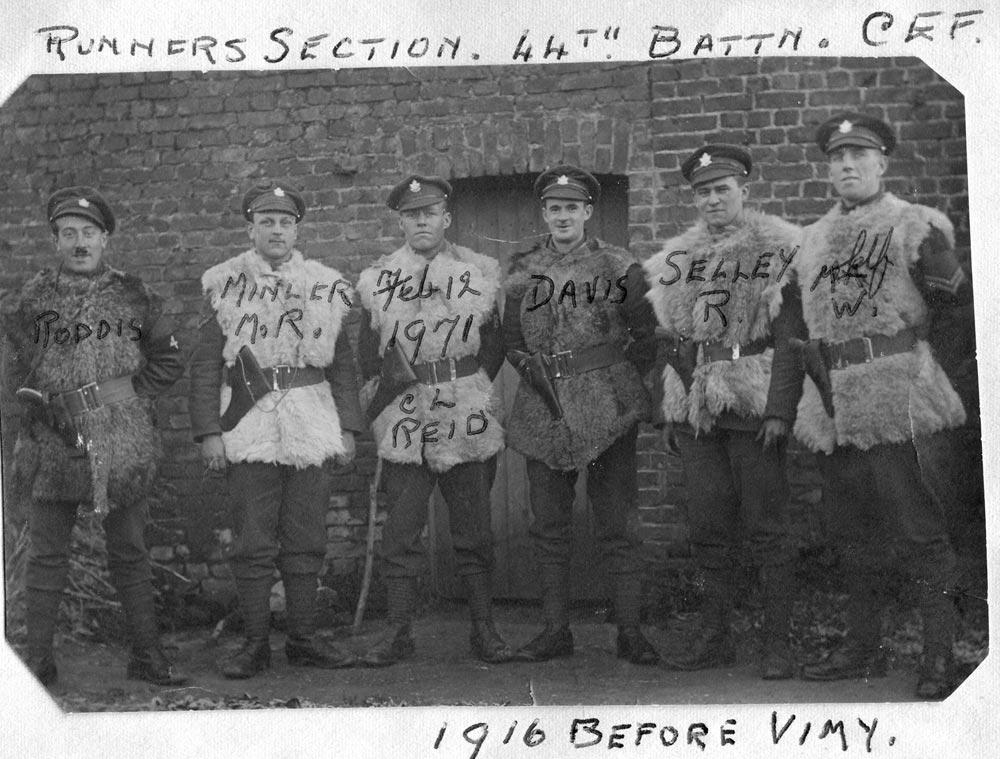

Pte May would join his brother at the renamed Camp Hughes that same year as Canada prepared its soldiers for overseas, including the Battle of Vimy Ridge in 1916 that was being planned for April 1917. Both served with the 61st and 44th Battalions, the latter part of the scout section.

Writing postcard letters was the norm for Pte May after he arrived overseas, with brother Harold and him posing for photos to send home to his wife “Betsy.”

In one written on Dec. 7, 1916, he wrote: “Just received three letters from you, written in Oct and 3rd Nov, a little late but nevertheless very welcome, will write as soon as possible in the meantime what do you think of your old pal, notice the aggressive attitude the same old ready for a row look eh, well dearest old girl hope you are all in the best of health and spirits, and that you have … time at Xmas. I am glad you got the photos.”

The photo in question on the front of the postcard has Pte Bill May standing with a cigarette in his right hand, his brother Harold in a fur coat and a cigarette in his left hand, with a seated comrade wearing an army long coat.

Besides serving in the Battle of the Somme, both brothers fought at the Battle of Vimy Ridge starting on April 9, 1917, where Pte May was wounded in the leg by shrapnel, while Harold received a nasty blow to his cheek, chin and shoulder after a bomb went off near him. According to Mowbray, he was passed over when the medics came for the wounded, thinking his wounds were mortal.

“Three days later, he was found in the mud alive,” she recalled the story passed down by relatives. “He was taken to the hospital and was one of the first recipients of reconstructive surgery. [Harold’s] zest for life remained until his death [on Nov. 10] in 1951.”

Pte May would recuperate from his war wound in the “massage department” of the military convalescent hospital at Woodcote Park, Epsom.

In a letter he wrote home, dated on Aug. 8, 1918, there was not much information shared about his wound with wife “Betsy” as he recuperated: “… let you know I’m still kicking around here. Will soon be on [leave] pass am going up to see Scotts for a day or so. Up to Corsock.”

Pte May was referring to his road trip to the Village of Corsock in Scotland while he recovered from his shrapnel wound.

Following the end of the Great War on Nov. 11, 1918, after returning to the family farm, Pte May would raise a family of seven, including three sons who all enlisted in the Second World War. Son Harold, 23, was KIA in Holland on Feb. 8, 1945. Eldest son Walter died in 1971 after saving a co-worker’s life.

After moving to Camp Shilo, his remaining sons worked the farm, while daughters Margaret, Joyce and Dorothy joined their parents in the new PMQs being built for military families after 1947.

In charge of the YMCA, now a civilian, May helped the soldiers training for the Second World War with movies, library, sports equipment, canteen service and the Legion. During this time, Camp Shilo also housed German POWs — they were tasked with cleaning on the Canadian Army’s training Base.

After the Second World War ended, according to Mowbray, Maple Leaf Services hired her grandfather to manage the Ubique Theatre — now L25 — in 1946. Besides being the projectionist, he was also the Base’s Justice of the Peace starting in 1952.

Retiring on Oct. 12, 1961, and moving to Binscarth, May never slowed down. Mowbray said her grandfather was thrifty, and never owned a car. On the Base he would walk or ride his bicycle. If he needed a car, he had friends who would lend one.

May’s grandkids Kelvin and Kathleen said their grandfather was not one to share stories of the carnage from the Great War battlefields where he fought, but on occasion if he was sharing war stories with old comrades, if they listened intently they might hear something he did not readily share with the family. Like what it was like fighting the Germans during the Battle of Vimy ridge 106 years ago.

With the scrapbooks, they were able to to view his experiences in the photos he took, or purchased as postcards while at Camp Hughes and during his time in France.

• • •

The need for a central training camp in Military District 10 (Manitoba and Northwest Ontario) resulted in the establishment of Sewell Camp in 1910, on Crown and Hudson’s Bay Company land near Carberry. The site was accessible by both the Canadian Northern and Canadian Pacific Railways and the ground was deemed suitable for the training of artillery, cavalry, and infantry units.

The first summer training camp, in 1910, was attended by 1,469 soldiers. Militia soldiers continued to train in the summers up until the final pre-war camp in July 1914.

After the formation of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) in 1914, the camp was expanded to train the large numbers of new recruits. In 1915, 10,994 men of all ranks attended camp, including Pte Harold “Polly” May. Permanent buildings were constructed, a rifle range with 500 targets was set up, and the water supply was improved.

In September 1915, Camp Sewell was renamed Camp Hughes in honour of Canada’s Minister of Militia and Defence, MGen Sam Hughes.

In 1916, the camp trained 27,754 troops, including Pte Bill “Ning” May, making it the largest community in Manitoba outside of Winnipeg. Construction reached its zenith, and the camp boasted six movie theatres, numerous retail stores, hospital, large heated in-ground swimming pool, Ordnance and Service Corps buildings, photo studios, post office, prison and many other structures. The troops were accommodated in neat groups of white bell tents, located around the central camp.

The Camp Hughes trench system was developed in 1916 to teach trainee soldiers like the May brothers the lessons of trench warfare which had been learned through great sacrifice on the battlefields of France and Flanders. Veterans were brought back to Canada to instruct in the latest techniques. The trenches accurately replicated the scale and living arrangements for a battalion of 1,000 men.

The battalion in training would enter the system, after first being issued their food, ammunition and extra equipment, through two long communication trenches which led up to a line of support and front-line trenches. All along the route dugouts with thick earth overhead cover housed the troops and protected them from artillery fire.

Once established, the battalion would undergo training in daily routine, sentries, listening posts, trench clearing, and finally, a frontal assault on the “enemy” by going over the top and across no-man’s-land into the enemy line of trenches.

The shallow “enemy” trenches were built on higher ground as were most of the German positions on the Western Front in Europe.

An additional trench system served as a “grenade school.” Here, troops would practice working their way down an enemy occupied trench and finally throw live grenades from the trench into pits dug near the end.

Though much eroded after a century, the trench system is still essentially intact and is the only First World War training trench system extant in North America.

A decline in voluntary enlistments — culminating in the Conscription Act — caused the suspension of training in 1917 and 1918 and closure of the now historically designated provincial and federal park.

Before leaving for France to face the Germans in the Battle of Vimy Ridge 106 years ago, brothers Harold (sitting) and Bill May trained for their Great War experience at Camp Hughes in 1916. Assigned to the 61st Battalion with the Winnipeg Rifles, Bill May was wounded by shrapnel to the leg during the Battle of Vimy Ridge. His older brother was left for dead on the battlefield after a shell exploded nearby and his cheek, chin and shoulder sustained horrific wounds. Three days later, he was found in the mud alive when fellow soldiers were out picking up corpses on the battlefield. Harold May was one of the first recipients of reconstructive surgery. Pte Bill May quenches his thirst in a trench dugout prior to the battle of Vimy Ridge on April 9, 1917. The May brothers posed for a number of photography postcards during breaks from training in England, and later France. Photo studios were set up and Canadian soldiers often used them so they had something to send home to family. It was against military law to take photos on the battlefield. Only military photographers hired to catalogue burials, were allowed to carry cameras on the front lines. Photos courtesy grandchildren Kathleen Mowbray/Kelvin Schrot