Editor’s note: Then Capt Douglas H. Gunter wrote a diary during his early days posted to Camp Shilo, arriving here in the fall of 1946. He would have three postings to this Base, 11 years apart, including a stint as BComd from 1969 to 1970, with wife Jo and their two children Richard and Anne. Retiring after 32 years with the Royal Regiment of Canadian Artillery, he died on March 4, 2005 in his 84th year. A graduate from the University of New Brunswick in 1942, he then saw action in the Second World War during operations in Northwest Europe (12 Field Regiment RCA), followed by Korea and peacekeeping duties in Cyprus. He held various command and staff appointments including Commander of A Battery, RCHA; Brigade Major 3CIBG; Commandment Canadian School of Artillery as well as CFB SHILO BComd. He was Director of Land Requirements and Director of Artillery on retirement in 1974. He then became executive director of the Canadian Figure Skating Association serving in various capacities for 17 years.

Col Douglas Gunter

Stag Special

The Queen is coming to Shilo! The Queen is coming to Shilo! The news spread like wildfire among the 4,000 inhabitants of this military community on the old Yellow Quill Trail, a westward bound wagon route in the middle of nowhere.

Actually Shilo is a military base, more appropriately a “camp,” situated on the bald prairie about 25 miles southeast of Brandon in Manitoba. It boast 125 square miles of barren terrain not suitable wheat and includes the only “living desert” in Canada.

Because of its wide open spaces, Shilo has become, during and since World War II, the Regimental Home of the Canadian Artillery, a center for parachute training and parachute packing and, more recently, a live firing training area for armoured unit of the German Army.

As a long time artillery officer, I found myself and my family posted to Shilo on three separate occasions since 1946, each eleven years apart. I liked the place because it was a great training area, had good hunting and fishing, but my family had some reservations about this isolated reservation. Now I was finishing a tour as Base Commander and we were about to move on posting to Montreal in the spring of 1970 when word of the Royal arrived, together with a request that I remain in Shilo to play host.

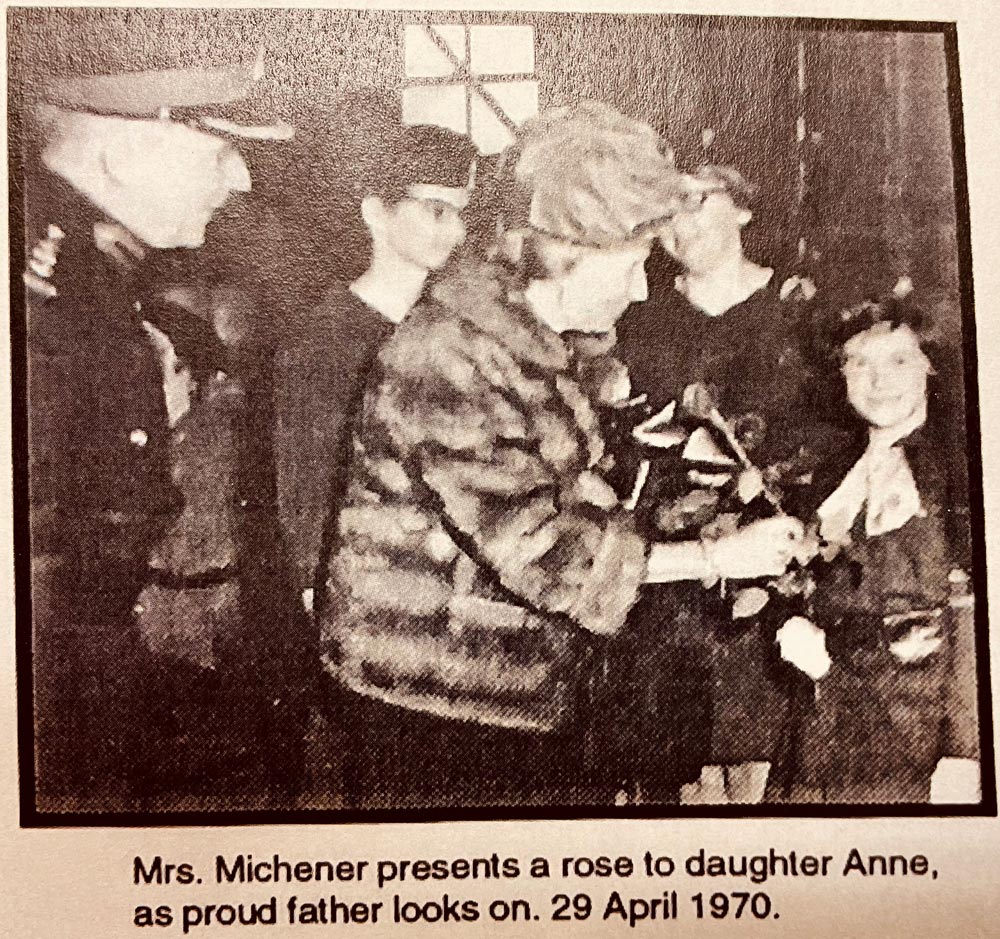

In fact, we had a number of visits by VIPs at this time, including one by the Governor General Mr. Michener and his wife in April 1970, so we were sharpening our hosting skills.

Never the less, detailed planning for the Royal visit became a protracted procedure, with many letters, messages and visitors arriving from Ottawa. Among the matters to be sorted out were the program for the visit, protocol, administration arrangements, and, of course, security.

I found that, as Base Commander, I had little input into the program, which was essentially determined in Ottawa. It was to consist of an air drop by soldiers of the Canadian Airborne Regiment from Edmonton, and demonstration of free fall parachuting and rappelling — more on that later.

There will also be a display on Arctic warfare equipment, at the personal request of Prince Philip. I wanted to add a presentation ceremony by the Queen of commission scrolls to six young officers who were just qualifying for their commissions in Shilo. I also requested that we plan an alternative program in the event of bad weather — some event under cover.

Both proposals were turned down on bureaucratic or security grounds. This lack of “wet weather” program became more significant as events unfolded.

The Royal visitors to western Canada in 1970 would be Queen Elizabeth, Prince Philip, and their children, Prince Charles and Princess Anne. They were to travel across the prairies by train — in fact by two trains to accommodate the media. Shilo was to be the only military event in their itinerary and, in fact, it evolved that they were coming to Shilo not one, but twice.

The first time was simply to rest overnight in a train stopped on the Shilo railway siding — no real involvement for the Base. Th next morning they would leave by train to visit Dauphin, returning to visit Shilo in two days time. However, as the event grew closer, a possible complication arose, in that a CN Rail strike was threatened and there was concern that the sleeping cars might not be in position in Shilo in time to accommodate the Royal visitors.

This was explained to me during a phone call from General Cooper, the Canadian officer in Ottawa, co-ordinating the tour. He went on to ask if the visitors could be accommodated in Shilo, if the train didn’t arrive. I replied, “We have no hotels in Shilo but would be pleased if they staying in our officers’ mess — not luxurious but adequate for one night.”

The immediate response was, “It would be more appropriate for the Base Commander to make his residence available.” When I subsequently told my wife and children that we might be moving out to make room for royalty, the children thought that would be exciting, while my wife, with her Irish heritage, was less enthusiastic.

In preparation for this eventuality, the security people went over our house with a fine tooth comb and pronounced it safe. However, no one installed brand new mother-of-pearl toilet seats, contrary to the then current rumour — probably started in the men’s canteen. In any event, the sleeping cars arrived in time and we didn’t need to vacate.

The big day of the Royal visit to Shilo, 13 July 1970, started sunny and warm with a gentle breeze. The latter is especially important if you’re planning to jump out of airplanes, when a high wing makes this downright dangerous. Th Royal train was due to arrive at noon at the whistle stop Shilo station, near the Village of Douglas, ten miles north of Shilo.

From there a motor convoy would bring the visitors through the Base and directly out to the demonstration site some two miles south of the townsite on the open prairie.

By mid-morning I decided to have one last look at the demonstration site. It now consisted of four stands, all facing the open prairie — the Royal Enclosure, VIP Stand #1, VIP Stand #2 and a stand for the general public. There was also a display of Arctic equipment, with manikins (sic) dressed in winter warfare clothing and even an igloo for realism, built of white plastic blocks.

We had spent days working out the correct protocol for the seating plan as the event would be attended not only by royalty and their personal staffs, but also by senior military and government representatives. There would be the commander of Mobile Command, Lt Gen Gilles Turcot and his wife, the Federal Minister of Supply and Services, the Honourable James Richardson and Mrs. Richardson, the Member from Brandon-Souris, the Honourable Walter Disdale and wife, the Mayor of Brandon and wife, to name a few.

I noted with satisfaction that each chair had been properly labelled with the name of its intended occupant in beautifully hand-lettered India ink. The whole place had a festive air with much bunting gently undulating in the breeze (bunting which had cost our Base fund $7,000, I thought ruefully).

Already several thousand of the local citizenry had turned out and were milling around. There seemed to be children everywhere playing happily as they waited for the big show.

I stood in the empty Royal enclosure surveying this happy, festive scene, somewhat smugly, when suddenly I noticed a large black cloud on the distant prairie horizon. It looked like a thunderhead and appeared to be moving rapidly in our direction.

I was incredulous — no such storm had been forecast for today! Nevertheless, the threatening cloud soon descended on the demonstration area with lightening, thunder and pelting rain. Vicious winds were soon blowing chairs, bunting, igloo and children horizontally across the prairie.

I tried to help some parents hold down their children but soon realized there was little I could do to retrieve the situation.

In the best Army tradition, I left the sergeant major in charge and drove to the nearest telephone, hoping to delay the Royal train until the storm abated or perhaps even stop it. I dialled the number of the mobile phone on the train several times but could only elicit this operator response, “I’m sorry sir, but that phone is out of order!” Eventually time ran out and I had only time to pick up my wife and to meet the Royal visitors at Shilo station.

The train arrived on time but in heavy rain. After the welcoming formalities we got the convoy away toward Shilo and the demonstration area, but at the slowest possible pace. I took off separately in my car taking a shortcut at top speed. Although the storm was easing, its damage was clearly apparent as I arrived at the site.

The pole which was to bear the Royal standard had collapsed, cutting the overhead awning in two, as it tumbled to the ground. The severed, soaked cloth flapped listlessly in the rain. Soldiers were setting up chairs again and trying to swab them dry with rain-soaks rags.

I noted that the once attractive name tags were now illegible, black blobs. Someone had had the initiative to throw a red blanket over the Queen’s chair. I touched it with my finger and it squirted a jet of water back at me.

But now the convoy was arriving. I approached the Queen and asked her to remain in her car until we got the situation sorted out. Her response was, “We can’t be having that” and she entered the enclosure standing in front of her red blanket, waiting for the demonstration to commence. I spent the next few minutes getting people arranged in the stands in protocol order, insofar as I could remember it. Fortunately, the wind and rain soon eased so that the demonstration could begin on time.

The first event was a free fall drop from 12,000 feet of 18 paratroopers using special colourful chutes. In spite of lingering rain, they came through the clouds and landed right on target.

I was seated now standing between Prince Philip and Princess Anne. At some point during the free fall, [Princess] Anne decided that she would sit down. I heard her faint yelp and looked over to see a soldier’s fist gripping a wet rag sticking between her legs as she tried to sit. She leapt u and tried to regain her composure.

I didn’t dare look back to identify the owner of the fist who had tried to dry her seat as a critical time — no doubt he’s still retelling the story.

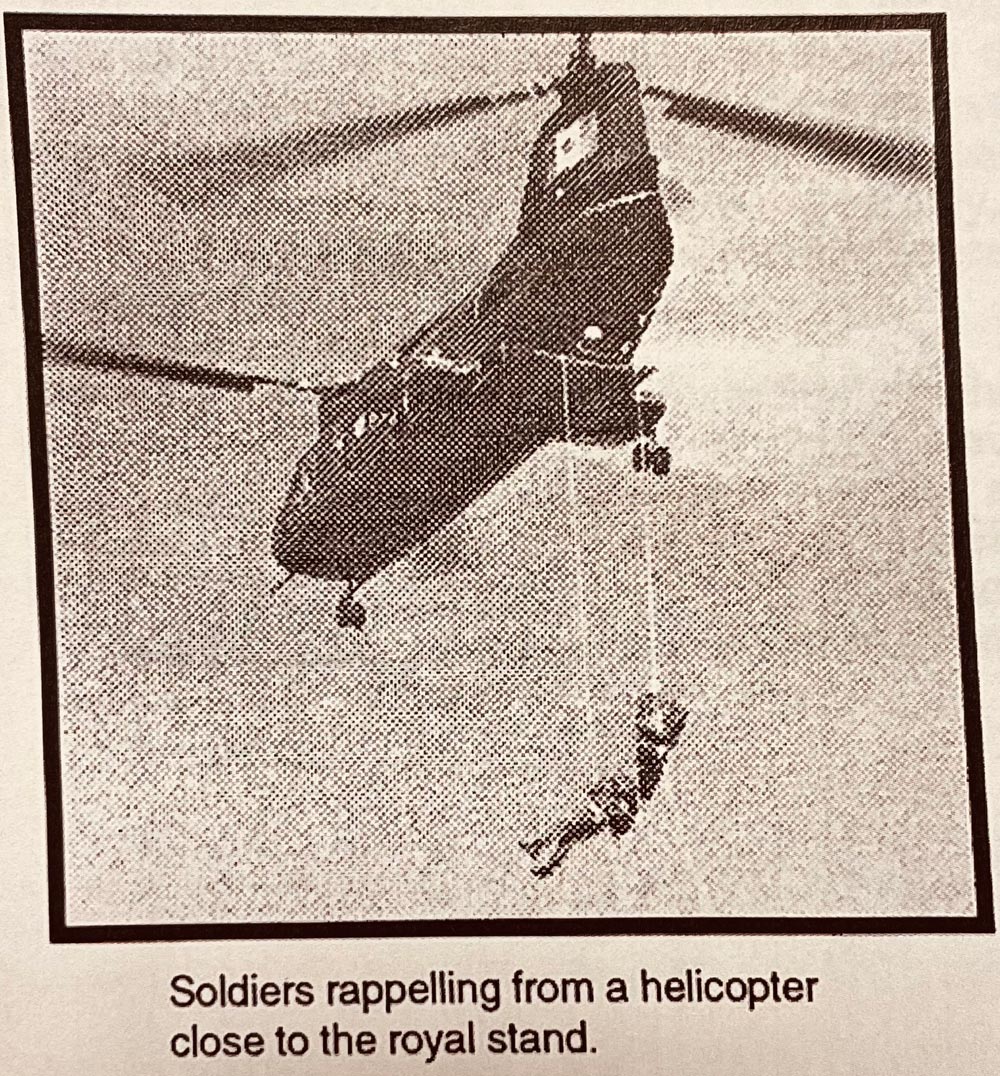

Rappelling is a technique whereby soldiers exit a hovering helicopter by sliding down ropes to the ground below. It is used tactically when the helicopter can’t land due to rough terrain, swamp, etc. One of the two helicopters demonstrating this technique got rather close to the stand hovering in the air as soldiers slid to the ground. The backwash from the rotor blades hit the Royal enclosure with a prolonged and strong blast of air.

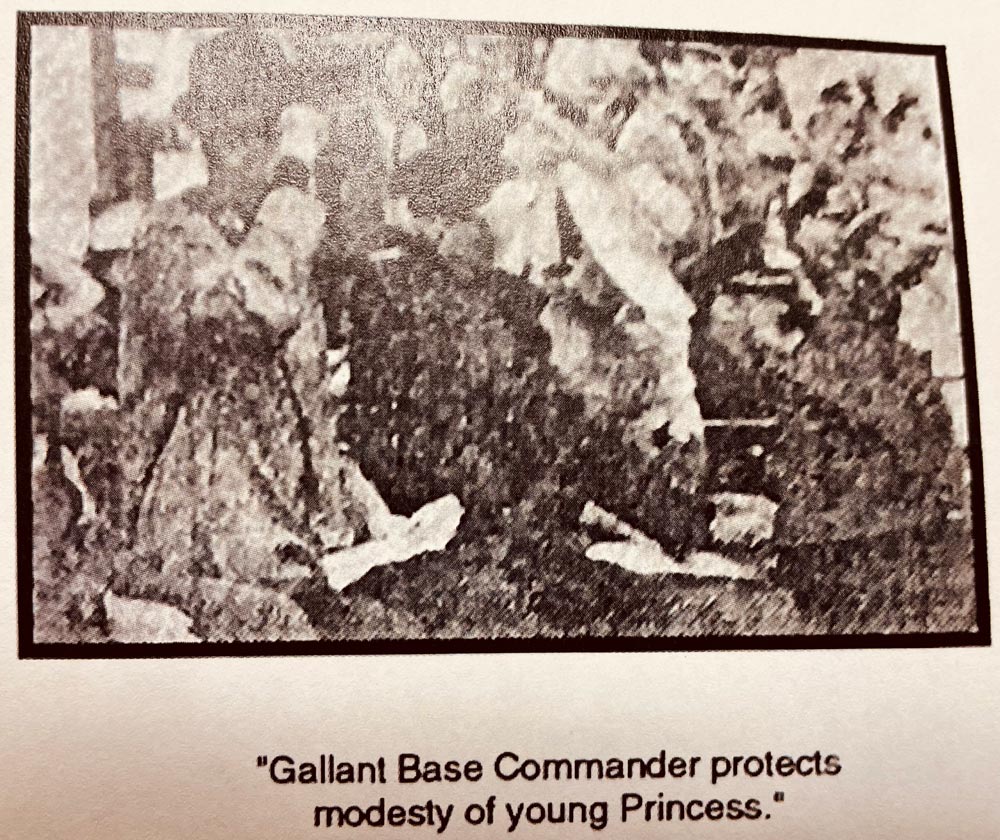

Princess Anne was trying to hang on to her hat while her lime green mini-skirt was flying in all directions. The ever alert members of the media rushed with their cameras to the front of the stand to capture the Royal thigh on film. I tried to thwart their efforts by holding an umbrella in front of the Princess.

In any event that was the picture that appeared in all the British and Canadian papers — me and [Princess] Anne and a black umbrella.This provided the angle that the press are always looking for in a story — “The gallant Base Commander protecting the modesty of the young Princess.” “Not since the days of Sir Walter Raleigh, 400 years ago has such gallantry been seen,” etc, etc.

The main event, the mass parachute jump from 1,200 feet by 350 soldiers of the Canadian Airborne Regiment, went without a hitch. Following the drop the troops formed up in front of the stands, were inspected by the Queen and gave a rousing three cheers for Her Majesty.

Next was a visit to the winter warfare equipment display, in which Prince Philip showed particular interest, asking many perceptive questions.

Finally, we left for the train at Shilo Station where we said our goodbyes. The Royal visitors waved from the rear platform as the train departed and the sun finally came out. It was a big day for Shilo but, as I breathed a sigh of relief, I resolved never again to become involved in an event so dependent on the weather.

This image from Toronto Star photographer Doug Griffin during the Queen’s visit to Manitoba. The original Toronto Star caption read: Hanging onto their hats to ward off wind, sand and rain sprayed by the whirling blades of a Canadian Armed Forces helicopter during exercises at Camp Shilo, Manitoba; the royal family sit on reviewing stand with officials. From left, Queen Elizabeth, Col R.G. Therriault, commander of paratroop battalion; Prince Philip, Col Douglas H. Gunter, commanding officer of Shilo Base; holding umbrella over knees of Princess Anne. Despite a thunderstorm which almost cancelled plans, the royal visitors watched a scheduled air show and drop by paratroops.

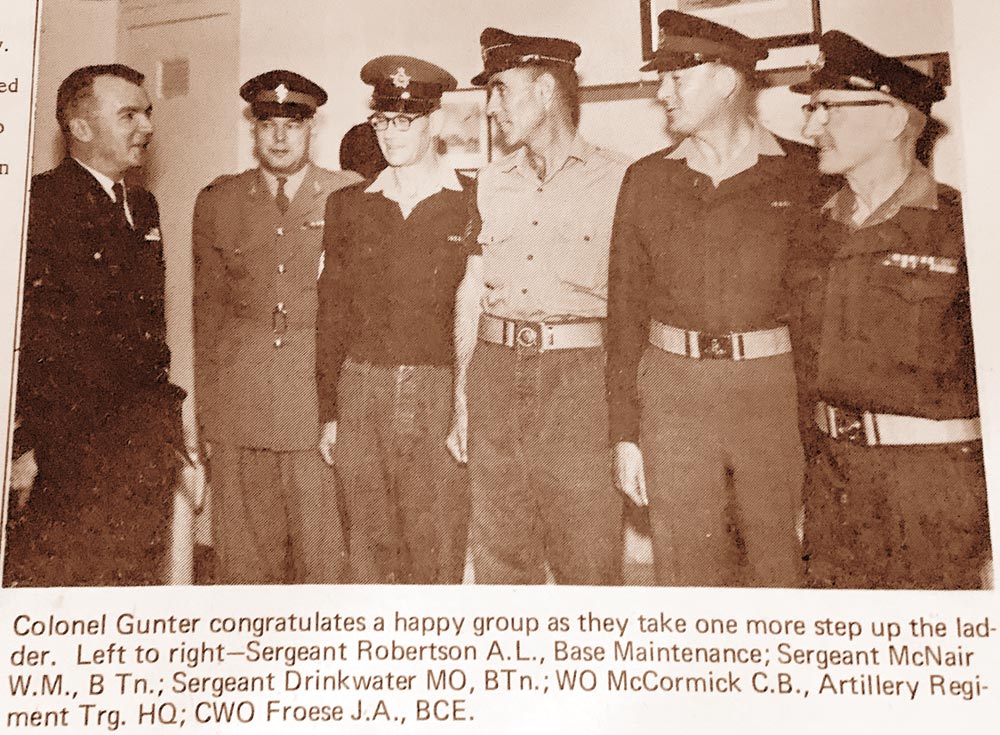

Col Douglas Gunter included a number of photos from the Queen’s visit in his diary, with his story covering pages 40 to 43. Plus, including here photos from the Shilo Stag during his tenure as Base Commander for one year prior to his departure in July 1970.