Photo: SUPPLIED: Canadian Press war correspondent Ross Munro typing a story in the field in Italy, August 1943 (Library and Archives Canada).

Submitted by RCA Museum, By: Johnathon Ferguson, First Published in Gunner 2021

The 80th anniversary of D-Day is commemorated across the globe today.

D-Day, as it has come to be known, drew together Allied troops with land, air, and sea forces as the largest amphibious military invasion in history. The operation started the liberation of France and Western Europe during the Second World War to lay the foundations of the Allied victory on the Western Front.

More than 150,000 troops landed or parachuted into the area on D-Day, including 14,000 Canadians. More than 10,000 Allied casualties were documented, with 4,1414 confirmed dead. German casualties are estimated to be between 4,000 and 9,000.

Canadians held a key role in the Allied Invasion of Normandy, codenamed Operation Overlord with 359 killed on D-Day.

Below is an article written by Johnathon Ferguson published in “The Gunner” for your reading:

Quick: Where did the Canadians land during the invasion of Normandy on June 6th, 1944?

Most readers of Barrage would be quick to answer “Juno Beach,” and many could go on to name the other beaches where British (Gold and Sword) and American (Utah and Omaha) forces landed. But what if you asked a Canadian soldier where he was headed as he waded ashore that day? He might have given one of several answers, but probably not “Juno Beach.”

I recently read Ross Munro’s Gauntlet to Overlord (1945), which was the first overview of the Canadian Army in World War II to be published.

As a war correspondent for the Canadian Press, Munro landed at Bernières-sur-Mer on D-Day with the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division’s Tactical HQ. His gripping, first-hand account of that fateful morning describes where each unit went ashore relative to the Norman towns and villages on the coast.

The lack of a reference to Juno Beach struck me as I read this, but I assumed it was because of operational security. Munro was privy to high-level briefings, and I reasoned that the beach code names were a secret in 1945.

The first official history of the Canadian role in Normandy was published just a year later and did not shy away from using these names. In 1946, Col C. P. Stacey, the Director of the Canadian Army’s Historical Section,

published Canada’s Battle in Normandy. It was one of three short

volumes describing the Italian campaign and Canadian

activities in the UK.

In this work, Stacey describes the landing area: “The Canadians’ sector went by the general code name ‘Juno.’ They were to assault on two beaches known as ‘Mike’ and ‘Nan,’ lying athwart the mouth of the River Seulles” (p. 45).

Like the British and American beaches, Mike and Nan were named after letters in a phonetic alphabet. Today, they would be called Mike and November beaches.

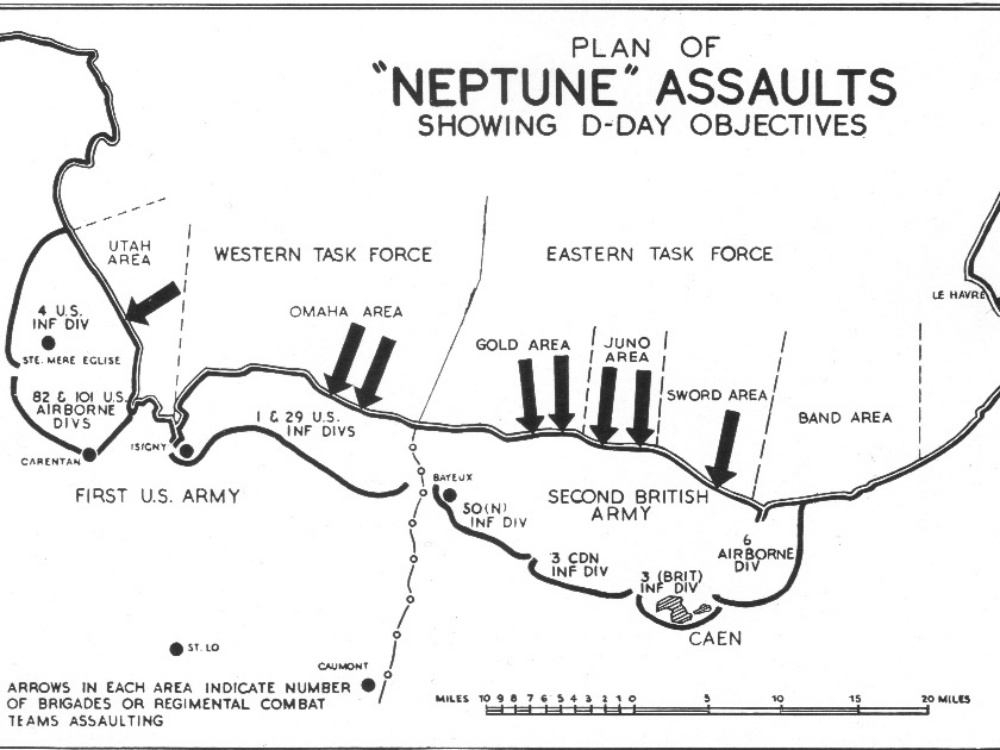

A map on page 42 of Canada’s Battle in Normandy shows the Operation Neptune assaults, as the landing phase of Operation Overlord was known. On this map, the Canadian objective is labelled “Juno Area.” In the official eyes of the Canadian Army, then, Mike and Nan were the “beaches,” while Juno was a “sector” or an “area.”

Col Stacey followed this up with a one-volume official summary of WW2 published in 1948 and called The Canadian Army 1939-1945. Despite the chapter dedicated to the planning and execution of Operation Overlord (pp. 168-184), Stacey here avoids code names and, like Munro

three years prior, locates the landings with reference to towns like St Aubin-sur-Mer and Courseulles-sur-Mer. The same is true for the map of the Normandy beachhead, opposite page 194. There is no mention of Mike, Nan or even Juno.

The Canadian Army completed a more detailed, four-volume official history of its involvement in WW2, with the D-Day landings covered in the third volume, The Victory Campaign (1960), also written by Col Stacey.

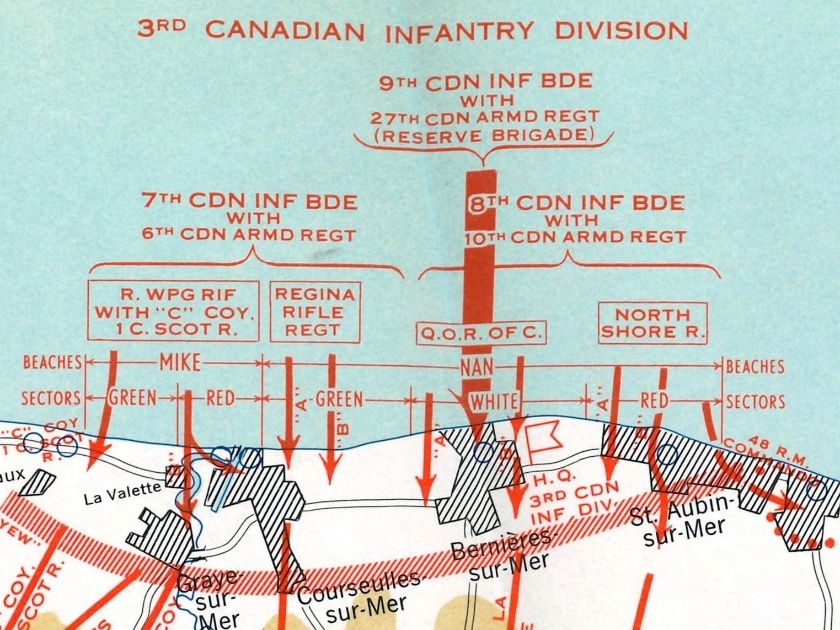

In this work, Stacey turns his 1946 terminology on its head: “… the

3rd Canadian Infantry Division … was to make its D-Day assault against ‘Juno’ Beach, in the centre of the sector allotted to the [British] Second Army. … The Canadian attack was to be made on a two-brigade front, through sectors known as ‘Mike’ (right) and ‘Nan’ (left), including

the villages of Courseulles-sur-Mer, Bernières-sur-Mer and the western outskirts of St. Aubin-sur-Mer” (p. 76). By 1960, it seems that Juno had become a beach, while Mike and Nan had become sectors of the beach, reversing the previous terminology.

Stacey continues calling Mike and Nan “sectors” in The Victory

Campaign, but the situation becomes more complicated when considering

their subdivisions. Planners divided Mike into two parts (Green and Red)

and Nan into three parts (Green, White and Red). They chose these

colours because they reflect the directional lights on an aircraft or

boat: green for the right, white for the centre, and red for the left. Stacey also calls these subdivisions beaches. For example, he writes that “The Royal Winnipeg Rifles … landed on ‘Mike Red’ and ‘Mike Green’Beaches …” (p. 102).

On the other hand, Map 2 in The Victory Campaign contradicts Stacey’s text.

This map of the Canadian actions on D-Day clearly labels Mike and Nan as “beaches” and their Green, WhiteA detail of the map showing the Canadian assault on D-Day from The Red subdivisions as “sectors.” In all, the terminology of this work is hopelessly muddled when it comes to these landing zones: Juno is a beach, Mike and Nan are sectors or beaches, and their colour-coded subdivisions are also sectors or beaches.

Of course, a beach can be any length of the seashore. Today, history and commemorations of the D-Day landings consistently refer to the Canadian objective as Juno Beach, regardless of whether that term was used in 1944. There is no “Juno Sector Centre” to visit, for example.

In the end, what has this foray into first-hand accounts and official histories provided us?

For one thing, it warns us that we need to be cautious when working with different sources because terms can change through time, even for

the same author. It also reminds us that history is a process of

negotiation that takes time, as society and historians digest the present into the past. Most importantly, for the Canadian soldier on that faithful June morning in 1944, whether his objective was called a “beach,” a “sector,” or an “area” was immaterial to the job at hand. Where was he headed? I like to think his answer would be “Berlin!”

Photo: SUPPLIED: Map of the D-Day Assaults from Canada’s Battle in Normandy,

showing ‘Juno Area’ (Stacey 1946: 42).

Photo Supplied: Victory Campaign, showing Mike and Nan Beaches and their sectors (Stacey 1960: Map 2).