Andrew Oakden

Jonathan Ferguson

Stag Special

They were three brothers in the First World War — they all died within one year of each other.

Pte Hugh Ross died on June 6, 1916 in Belgium; Simon Ross died on Feb. 22, 1917 in Mesopotamia; while William Ross died on May 1, 1917 in France.

They were the sons of Hugh Ross from the Highlands of Scotland, who immigrated to Canada in 1907 and settled in Manitoba, choosing Virden as home. He brought two sons to Canada, Hugh and William, a daughter, Mary, and a second wife, Jane.

The third son, Simon, did not immigrate to Canada.

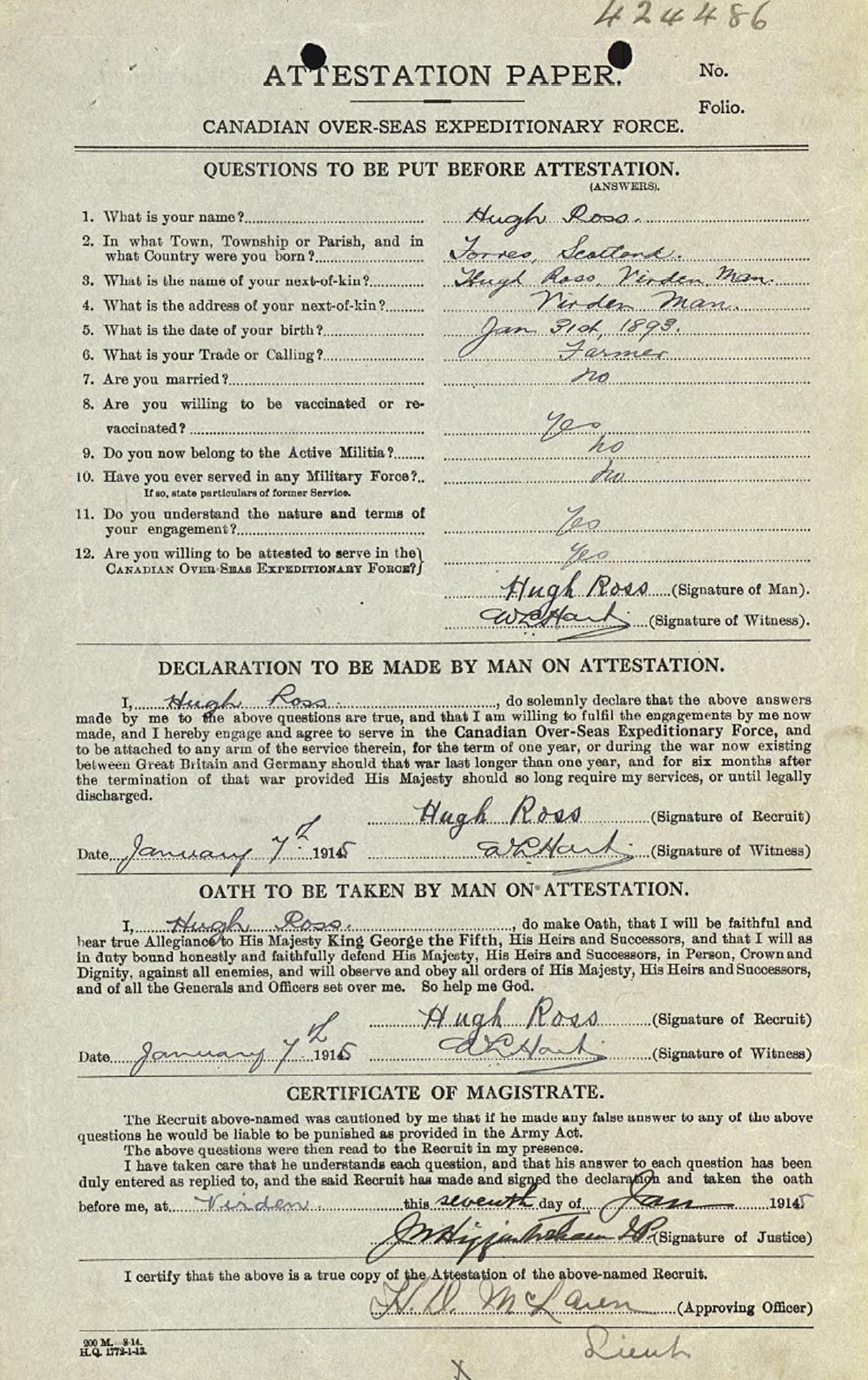

The youngest of the three brothers, Pte Hugh Ross, was born in Forres, Scotland in 1893. When he enlisted in January 1915, he was single and a farmer living in Virden. The 28th Battalion, Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF), took him on strength in February 1916. The 23-year-old died in action four months later.

He died early in the attack at Sanctuary Wood, a strategic hill in the Ypres Salient in Belgium. He was killed during the Battle of Mount Sorrel, with the Canadian Corps having heavy casualties from June 2 to 13, 1916.

On June 6, the 28th Battalion reported him Missing in Action (MIA), then six months later, the Canadian Corps listed him as presumed killed. On Jan. 10, 1917, the Brandon Sun had his name under war casualties. Canada never recovered his remains from the battlefield.

The second oldest, Pte Simon Ross, who never immigrated to Canada, joined the 1st Battalion of the Seaforth Highlanders before the outbreak of the Great War and went into theatre in France on Oct. 12, 1914.

The 1st Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders, served in India before the First World War, on the Western Front in France from 1914 to 1915, and then dispatched to Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) in December 1915.

In December 1916, the BEF participated in “the advance on Baghdad,” part of the Mesopotamia campaign, with 50,000 soldiers, most from India. In late February 1917, the British advanced on Kut to retake the city, which the British had lost in April 1916.

The British retook Kut from Ottoman forces on Feb. 24, 1917, then marched on Baghdad in March 1917. Pte Simon Ross died in action on Feb. 22, 1917 during the retaking of Kut at age 27.

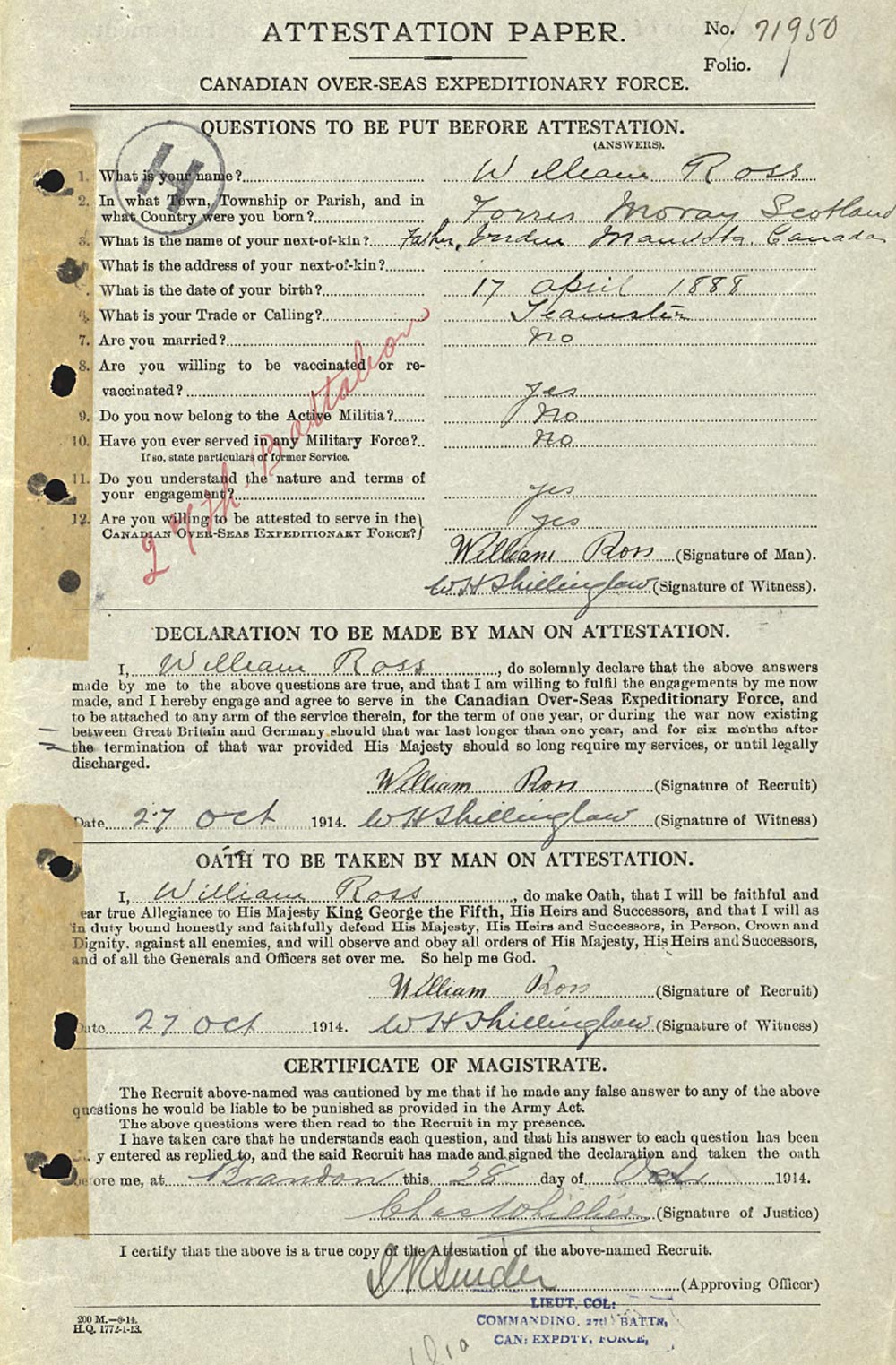

The oldest brother, A/LCpl William Ross, was born in 1888 in Scotland. Before the war, he worked as a teamster and lived on 8th Street in Brandon, MB. On Aug. 26, 1916, the Brandon Sun said he was “a wrestler of some repute, being a husky young athlete.”

He was single and enlisted on Oct. 27, 1914, sailed in May 1915, and went to France in September 1915. In February 1916, he fought on the Western Front with the 27th Battalion, CEF. On Aug. 9, 1916, the Germans wounded him in the left hand, then on May 1, 1917, he died in action in the trenches west of Fresnoy. Canada never recovered his remains from the battlefield.

The 27th Battalion War Diary lists 37 KIA, eight died of wounds, 186 wounded, and 36 missing during the lead-up to the attack on Fresnoy starting on May 3, 1917.

During the Battle of Fresnoy, May 3 to 7, 1917, at the village of Fresnoy-en-Gohelle, the Canadian Corps incurred 1,259 casualties. While the Canadians took the town within a few hours from the Germans, enemy forces shelled the village with an estimated 100,000 rounds of artillery, causing most of the Canadian casualties.

The RCA Museum displays the military decorations and memorial plaques — called Dead Man’s Pennies — of the Ross brothers. Mrs. T.J. Demers donated the photographs and military decorations to the RCA Museum in 1984.

Each soldier received the British War Medal and Victory Medal, with Simon also receiving the 1914 Star and William receiving the 1914-15 Star.

Museum staff thought all three Ross brothers were Canadian, but discovered we had incorrectly labelled Simon as Canadian. When we looked at their photos, Simon and William had Canadian infantry uniforms, while Hugh wore a Seaforth Highlanders uniform.

Previously someone had mislabelled the images of Hugh and Simon. Also, Simon received the 1914 Star instead of the 1914-15 Star. The Canadian infantry did not fight in France and Belgium until January 1915, after the eligibility date for the 1914 Star.

Interestingly, Simon fought in the Mesopotamian Campaign in modern-day Iraq. From a Canadian perspective, this is very unusual due to the Canadian Corps not participating in Mesopotamia.

Dead Man’s Penny is a term used to refer to the Memorial plaque given to the next-of-kin of British (BEF) and Commonwealth (CEF) soldiers killed in the Great War. The manufacturer made the plaque from bronze and featured an image of Britannia holding a laurel wreath and a trident. They inscribed the soldier’s name in raised letters on the plaque.

The term Dead Man’s Penny is believed to have originated from the resemblance of the plaque to a penny. The plaque was a way for the British government to honour the sacrifice of soldiers who died in the Great War and to provide some comfort to their families as a tangible reminder of their loved one’s service.

Commonwealth nations awarded the British War Medal to all officers and enlisted personnel of British and Imperial forces who served overseas from August 1914 to November 1918. They awarded the Victory Medal to those who received the British War Medal and entered a theatre of war from August 1914 to November 1918. They made the British War Medal out of silver and the Victory Medal out of bronze and suspended them from a ribbon. The ribbon for the British War Medal was orange with blue, black and white stripes at the edges, while the ribbon for the Victory Medal was rainbow-coloured.

The British and Indian Forces awarded the 1914 Star to officers and enlisted personnel who served in France or Belgium from August 1914 to November 1914 — end of the 1st Battle of Ypres. They issued the 1914-15 Star to soldiers who served in any theatre of war between August 1914 and December 1915 who were not eligible for the 1914 Star. Both decorations include a ribbon with red, white, and blue stripes.

News of the Ross brothers’ death likely spread in Virden and Brandon, but museum staff could not find a single article on the Ross brothers after their death. They appear to be a previously unrecognized set of brothers who died during the First World War.

Perhaps their father, Hugh Ross, did not want the story broadcasted or to talk about his unimaginable loss. The mother of the three brothers, Elsie Kynoch, died in Scotland in 1902, and never had to experience the sorrow of losing three sons to war.

Losing one child is a tragedy beyond words; losing two or more is difficult to comprehend. For these families, the Great War was not just a distant military conflict, but a personal tragedy which shaped their lives forever.

The families of those who died in the First World War were left to struggle with their grief. Mental health services were virtually non-existent, and many people found it difficult to talk about their feelings or seek support, and many families suffered in silence.

Despite these challenges, many families found ways to honour the memory of their fallen soldiers, including displaying their photos and decorations in their homes. Additionally, the Canadian government offered support to these families, including financial compensation and issuing service medals to honour their sacrifice.

Since the First World War, the stories of the families who lost multiple sons have been kept alive through films and other media. These stories help to highlight the terrible toll which war can take on families and the importance of remembering those who have made the ultimate sacrifice.

The families who lost three or more sons during the First and Second World Wars represent a tragic and poignant reminder of the human cost of war. We will never forget their sacrifice — their legacy will continue to inspire future generations. Lest We Forget!

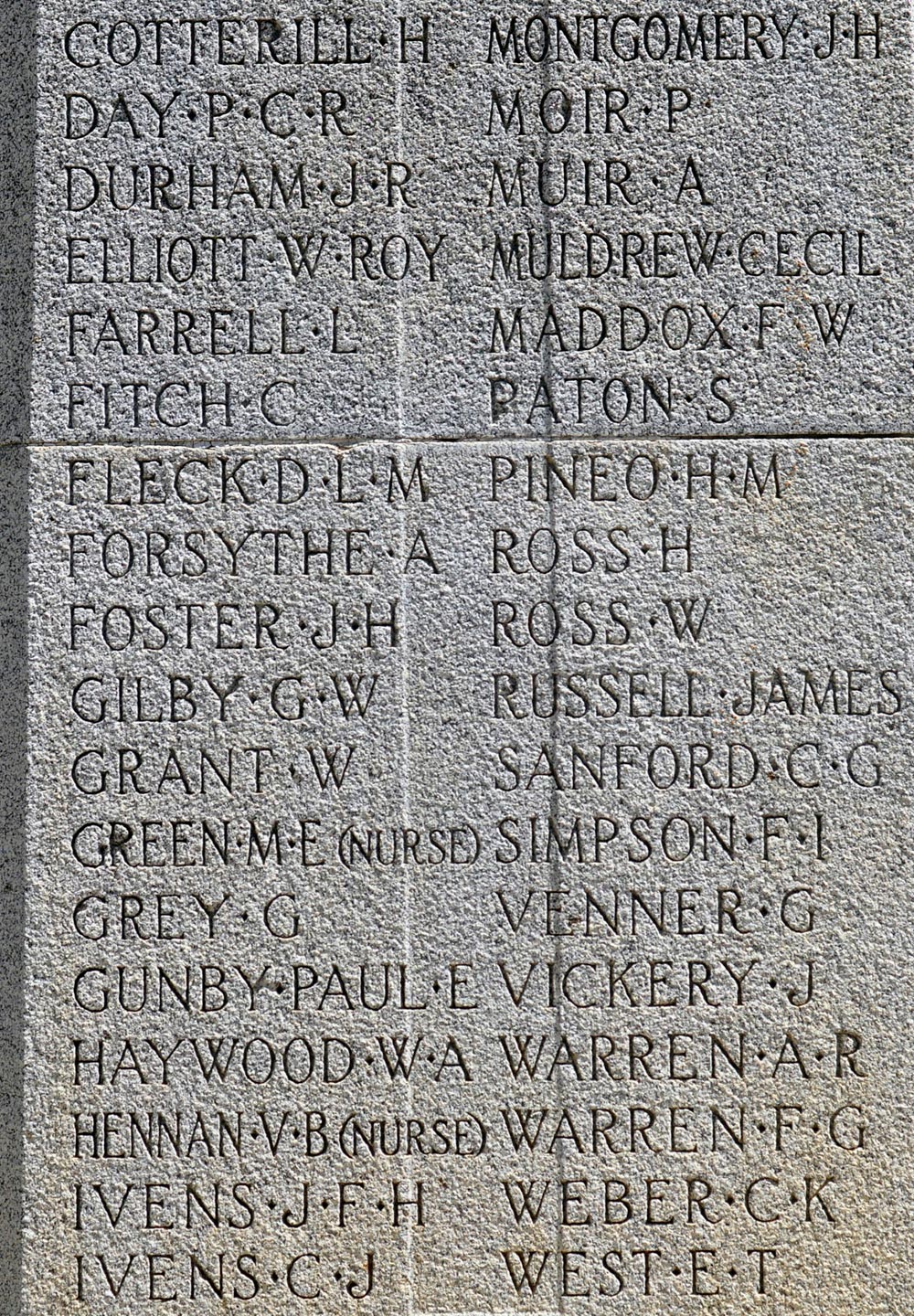

Virden’s War Memorial or cenotaph lists the names of Pte Hugh Ross and A/LCpl William Ross on the rear facade. Second World War names are on the front of the cenotaph. Photos Jules Xavier/Shilo Stag

Stop by the RCA Museum, and visit the Great War section, where you can see the Ross brothers’ military medals and the Dead Man’s Pennies their family received after all three siblings were KIA.

We found the attestation paperwork both Ross brothers signed when they enlisted in the CEF.