Jules Xavier

Shilo Stag

A veteran of the D-Day invasion in 1944 was laid to rest in Boissevain’s cemetery on a frigid winter afternoon.

It was a few days after his death at age 94 in January 2019 when Francis Godon’s family and friends gathered for his funeral.

It was a contrast to Godon’s experience on June 6, 1944, with B Coy 3 Div, when his landing craft finally reached a sandy beach in Normandy, France.

There were no birds softly chirping in nearby sun-soaked trees while family and friends gathered around his wood coffin, a handful of poppies sprinkled on the top. Seventy-nine years ago just after 7 a.m., Godon was running full out, often falling to a crawl, then quickly moving forward to avoid heavy German machine gun fire and mortar rounds on Juno Beach.

“Don’t let anyone tell you that you were not scared. You were scared,” he told an interviewer in a Veterans Voice of Canada (VVOC) interview in 2014. “On the beach, you had to go for yourself, which is hard to do when your buddies are crying out. You had to keep going. You had to stay alive [to continue the mission.]”

Godon acknowledged his objective was to clear the beach moving forward, taking out any German pillboxes which had escaped a constant pounding from warships out in the English Channel. B Coy faced the fiercest resistance on the beach that dreary morning.

The beach was defended by two battalions of the German 716th Infantry Div, with elements of the 21st Panzer Div held in reserve near Caen.

More than seven decades after experiencing his arrival at Juno Beach, Godon said he never forget the sounds of war, crying comrades with grotesque wounds scattered across the beach, or being struck by flying body parts.

“Crawl and run and crawl and run,” he told an interviewer for the Memory Project about his Juno Beach experience on the morning of D-Day. “If your buddies got hurt during that and the yelling and crying, you couldn’t stop. You had to keep going. If you stopped, well you were a dead duck, too. So you had to keep going. Which was a hard thing to do because the beach was something like ketchup … that’s how blood red the beach was.”

Juno Beach was one of five beaches of the Allied invasion of German-occupied France in the Normandy landings that day in 1944 during the Second World War. Godon and the 3rd Cdn Div’s D-Day objectives were to capture Carpiquet Airfield and reach the Caen–Bayeux railway line by nightfall.

In another interview for the VVOC documentary, Godon recalled the pep talk of an officer prior to the beach landing. That officer told his soldiers a lot of them would not be coming home. “So he said, ‘Just go to your job. Do the best you can. You are all trained. You know your job, so give ‘em hell.’”

Born on Aug. 19, 1924 in Dunseith, North Dakota, Godon died at 10:22 p.m. on Jan. 12. The father of three was 94. His wife Jane predeceased him on March 12, 2014.

He was five when his father left the Turtle Mountain region of North Dakota by wagon and relocated to southern Manitoba. In his youth, young Godon learned the ways of the Metis from his father — living off the land by hunting, fishing and trapping. Plus farming, with Godon recalling picking potato bugs daily when he worked in father’s potato field. Some of his survival skills helped him survive after being taken prisoner by the Germans four days into D-Day.

How did Godon find himself joining the Canadian Army to serve in the Second World War? It was not easy to enlist, he soon discovered. He was barely 17 when he was rejected three times. In his VVOC video, he told the interviewer “I was going there to fix Hitler” as a reason to enlist alongside other Canadians.

In a documentary done when he was in his 80s, by Aboriginal People’s Television Network (APTN) and CTV, with reporter Robert James at the helm, Godon said army recruiters dismissed his application because he was flatfooted, born in the USA or he had no formal education, plus spoke broken English. Persistence finally paid off a fourth time, when recruiters asked him to enlist as a French Canadian, not a Metis.

Sent to North Bay for his initial training, and with an idea of being part of the Lake Superior Scottish, Godon was tasked to do KP duty. It was not until he went on a long army march, after asking his orderly sergeant for the opportunity, did he finally receive a uniform, and could take up a rifle instead of a potato peeler. From North Bay, Ont., Godon was shipped to Camp Shilo, where he underwent further army training.

It was here he switched to the Royal Winnipeg Rifles, then was sent to Nova Scotia to finalize training prior to being shipped overseas. Besides honing infantry skills at Camp Shilo, he also was schooled in the operation of a “six-pounder” anti-tank gun. He was No. 1 on a six-man crew.

His voyage across the Atlantic was uneventful, besides dealing with ocean storms, because they had to avoid Germany’s prowling U-boats. He was never seasick, he recalled. He said he promised his mother he would return home from the war, a promise he kept despite the horrors on the beach on June 6, and his subsequent 11-month POW experience.

Because the Germans kept the POWs hidden from the Red Cross, with a long march deep into Germany that ended July 1, plus being sequestered in cramped box cars that moved on Germany’s vast rail network, Godon’s family received three letters from the Canadian Army about his whereabouts.

First, his family back in southern Manitoba were told he was missing in action (MIA); then he was presumed to be dead; and finally, he was dead somewhere on a battlefield in Europe.

Recalling his capture after four days in France, Godon said: “There were machine guns shooting at us, and we couldn’t get up. First thing I know, there was my lieutenant, waving the white flag. What could we do? [The Germans] said ‘for you the war is over.’”

The surrender need not have happened, according to Godon. He suggested a forested area might be a place for a German ambush, and B Coy should perhaps move in a different direction. This fell on deaf ears, and the lieutenant said move on. As a POW, Godon said he put on a brave face in front of his captors, and drew on his promise to his mother that he would return home.

The fear of beatings, or being shot, also kept the Canadian POWs in line. He recalled sleeping in fenced graveyards following the forced march for the next 21 days. Trying to escape was not an option.

“If you had one escape, [the Germans] would kill 10 of your buddies,” he said in the VVOC interview.

He did escape an early execution after Hitler’s Gestapo (SS) had the soldiers under guard. An SS commander who did not like the response he was receiving from interrogated POWs, who would only answer with their name, rank and serial number, had 23 soldiers merciless executed. He had his suspicions that his fellow POWs would be next, but a German officer stepped in and ended any further bloodshed.

He instructed his comrades to fight back and overpower the guards if they felt an execution was about to occur. “If you’re going to do, then why not do something,” he said in an interview.

In the APTN/CTV documentary, he recalled following his 11 months of captivity, before US soldiers liberated them from a POW camp, he weighed 212 pounds arriving in France, and 120 pounds by the time he was freed.

Put to work in labour camps, Godon saw work digging water and sewage lines with shovels. He also did farm labour, working in sugar beet and potato fields. And despite being fed “slop” by the Germans, he learned you did not try to eat raw potatoes if you were out in the field.

“If you did, they shot you,” he recalled observing this happen.

Reflecting on his time overseas fighting for our freedom alongside 22,000 other men who landed at Juno Beach, Godon said: “To look back we did something.”

This was evident when he returned to France in 2003.

“I saw what we had done,” he said of a beach now featuring young families and children playing on the shoreline, not fallen soldiers on a bloody beach in 1944.

However, life for the young soldier was never the same after he returned to Canadian soil. He fought for his veteran’s pension for 21 years before receiving it. Son Frank helped “smarten me up” after he relied on alcohol to drown out the war memories.

“We were not the same anymore,” he said of his war experience. “We were half animal, half human.”

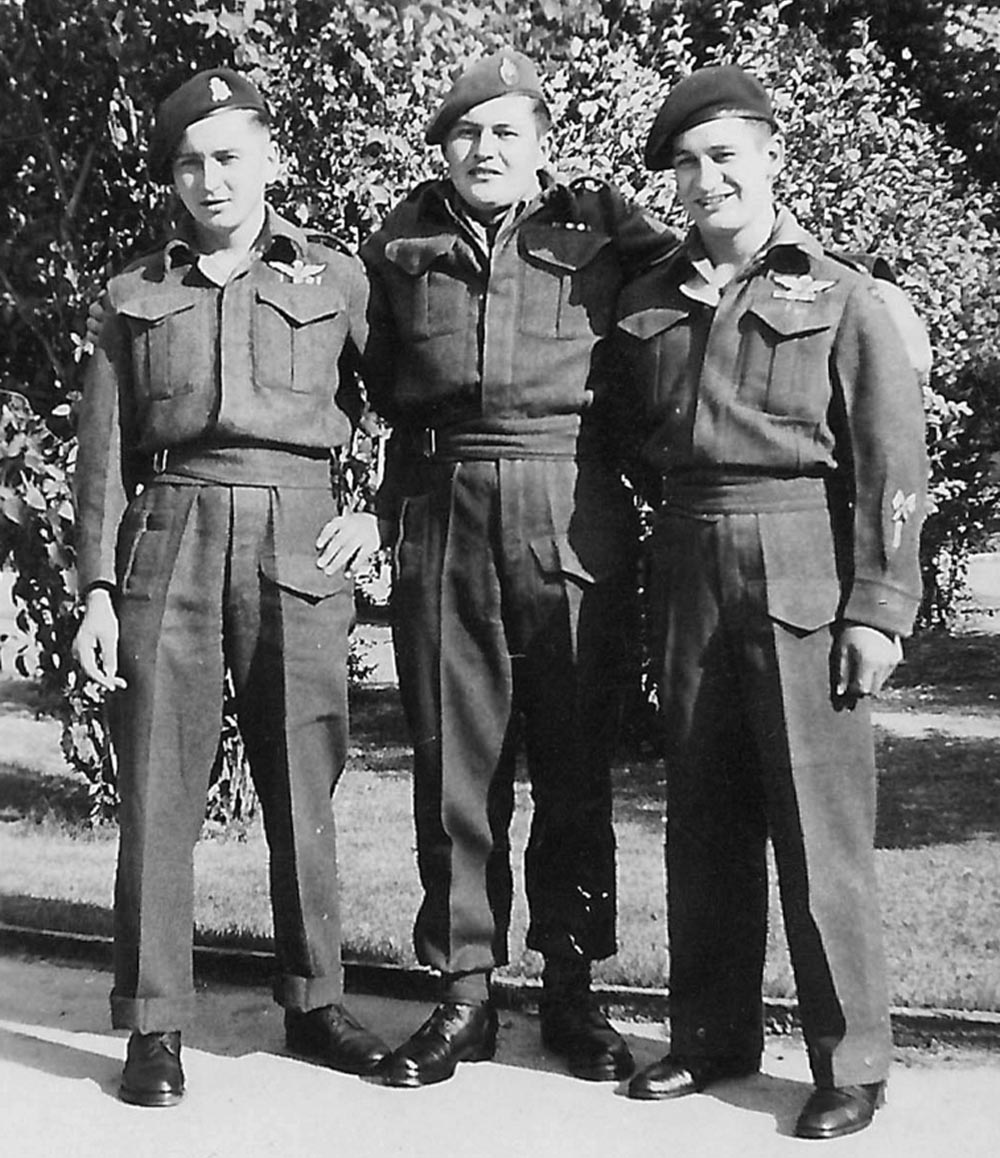

Covered in poppies, a photo of Frances Godon taken in 1942, when he was a young soldier, lays on his coffin following his funeral service on a frigid January day in Boissevain, Manitoba. During his return visits to Juno Beach decades later, Godon was still able to wear his military uniform. During his training at Camp Shilo in the 1940s, he posed for photos alongside his comrades who would see action in Europe during the Second World War. Photos Jules Xavier/Shilo Stag or supplied by family