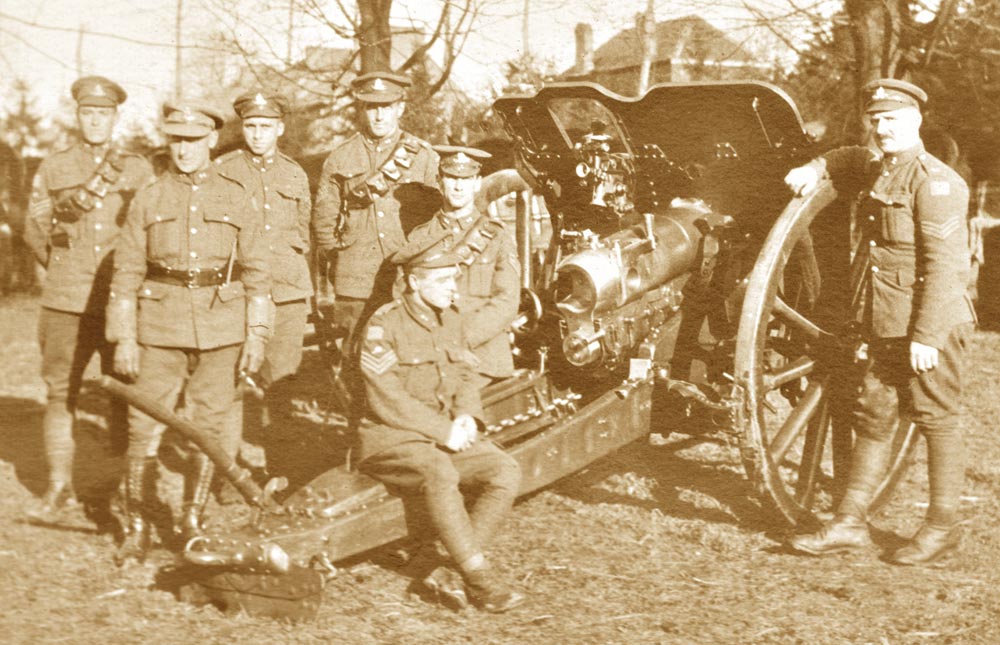

Officers and NCOs with 35th Battery and their 4.5-inch Howitzer in Mons November 1918

35th Battery Gun Park in Mons November 1918

Capt George A. Downey on horseback in Mons November 1918

35th Battery Officers’ horse lines in Mons November 1918

35th Battery’s horse lines in Mons November 1918

Andrew Oakden

Stag Special

Who were the Canadian volunteers which served overseas during the First World War?

By chance, I located in the museum archives an old album containing hundreds of First World War photographs belonging to Capt George A. Downey.

The collection includes excellent photos of the 35th Battery with 4.5-inch Howitzers in liberated Mons, Belgium, dated November 1918.

The Canadian military posted Capt Downey to the 35th Battery, 8th Brigade, 3rd Canadian Divisional Artillery — part of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) — in April 1916.

I also located a historical record of the 35th Battery mobilized out of Sherbrooke, Quebec, in August 1915.

In 1914, the Canadian Government created the CEF, a field force recruited from the civilian population which would go on and defend Canada overseas during the Great War.

The CEF existed within the Canadian Corps, composed of four Infantry Divisions, subdivided by brigades, each with infantry battalions, artillery batteries, and other specialized units attached.

Canada recruited 260 infantry battalions and more than 80 field and heavy artillery batteries. Most artillery recruits went to field batteries; a smaller number went to medium batteries and heavy batteries.

Each CEF field battery had four guns starting in December 1914, which increased to six guns in March 1917.

These soldiers fought in France and Belgium on the Western Front. From 1914 to 1918, more than 620,000 Canadians enlisted, with 425,000 going overseas to fight in the First World War.

The overwhelming majority enlisted as volunteers. Canada passed the Conscription Law in August 1917 — upwards of 24,000 Canadian conscripts went to France starting in January 1918.

The recruits came from different backgrounds, and most had never served in a military force or active militia. Many of the early recruits were unemployed.

English Canadians with loyalty to Britain made up at least half of the enlistment. French Canadians participated in lower numbers.

For example, many young men from Montreal joined the 35th Battery and went on to fight with 4.5-inch Howitzers in France and Belgium.

Minority populations volunteered for the CEF with an estimated 4,000 First Nations, more than 1,000 Black Canadians, and more than 200 Japanese Canadians, in addition to other groups such as Ukrainians.

In 1914, Canada accepted recruits between aged 18 and 45, with the average age being 26. Canada looked for healthy recruits standing at least 5-foot-3 tall — Gunners had to be at least 5-foot-7.

Each recruit went through a strict medical exam. Canada rejected many due to failed medical. Common reasons for non-acceptance included flat feet, poor eyesight and rotting teeth.

About 20 per cent were married with children. Regardless of their status, they all accepted the terms of enlistment “to serve in the Canadian Over-Seas Expeditionary Force,” until the war ended.

The Canadian Artillery equipped approximately 25 per cent of the Field Artillery with 4.5-inch Howitzers during the First World War. Canada had 15 howitzer batteries, including the 35th Battery.

After being raised, the 35th Battery spent two weeks in Montreal before moving to Valcartier for basic training, then shipped overseas to England, destined for France and Belgium.

Staff at the RCA Museum have on display one example of a 4.5-inch Howitzer which was in Canadian service from 1911 to 1941, replacing the BL five-inch Howitzer.

This gun was the main field howitzer during the First World War. It included a rifled steel barrel, sliding breech block, smokeless powder, a hydro-spring recoil mechanism and two-part cased ammunition for quick loading and re-firing.

The gun used a steel box carriage which enabled the barrel to rest between trails to a maximum elevation of 45 degrees. The high elevation allowed the howitzer to lob shells into enemy trenches.

It could fire 16-kilogram ammunition to an effective range of seven kilometres.

Comparable to other Canadian batteries, the 35th fought in many famous Great War battles such as the Battle of Ypres (1915), Battle of the Somme at Beaumont-Hamel (1916), Battle of Vimy Ridge (1917), Battle of Hill 70 and Lens (1917), Battle of Passchendaele (1917) and the Last Hundred Days (1918).

The CEF lost 60,661 soldiers during the First World War, representing more than nine per cent of the total CEF.

More than 170,000 returned home with serious wounds. Post-war, Canada disbanded the CEF and reorganized to a much smaller military force.

Canada did perpetuate some of the unit numbers, battle honours and histories of CEF units which had fought during the war.

The Gunners of the 35th Battery enlisted for up to four years of service in France and Belgium. They went through “togetherness” in good times and bad times, firing their 4.5-inch Howitzers on the Western Front until the Armistice on Nov. 11, 1918, and remained overseas until March 1919.

The lucky ones returned home to start families and build communities, and in some cases, saved their wartime memories in old photo albums.

At the museum, we safeguard photo albums and artillery artifacts, such as the Capt Downey collection and the 4.5-inch Howitzer, which reflect our proud history and heritage.