Douglas has a cenotaph on Hwy 340 adjacent to the curling club.

Retired RCA Museum senior curator Kathleen Christensen placed a poppy cross at the grave of LCpl James Kendall prior to an informal Remembrance Day ceremony at Camp Hughes’ cemetery.

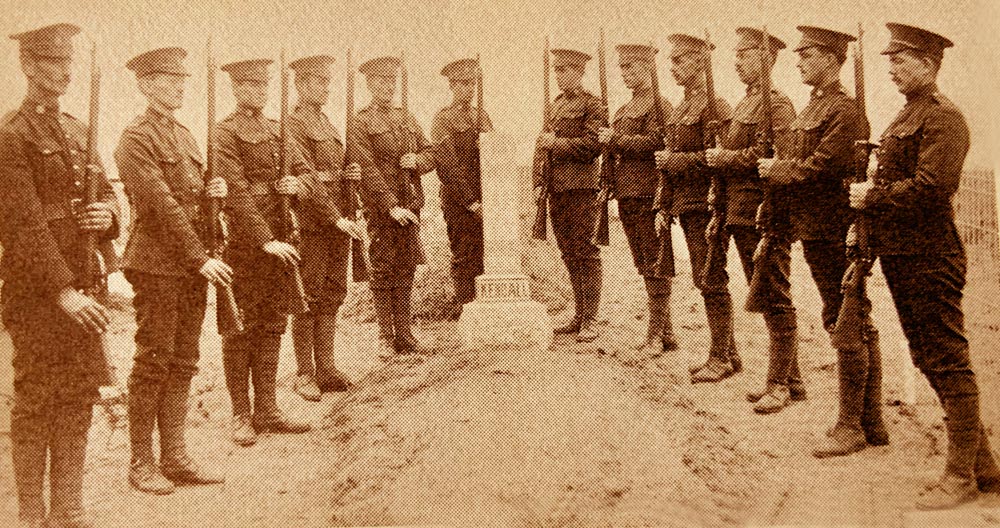

LCpl James Kendall had a full military funeral at Camp Hughes following his death on Sept. 12, 1916. He’s one of six soldiers who are buried in the training camp cemetery.

Then Maj Reg Sharpe paid respects at the Camp Hughes’ cemetery during a visit to the historic site. Photos Jules Xavier/Shilo Stag

The various graves of soldiers who trained at Camp Hughes, but died before they went overseas.

They dies unnoticed in the muddy trench,

Nay God was with them, and they did not blench,

Filled them with holy fires that naught could quench

And when he saw their work on earth was done

He gently called to them my sons, my sons.

— verse on Douglas cenotaph

Jules Xavier

Shilo Stag

When Douglas celebrated its centennial in 1982, the book Echos of a Century listed 11 residents of the community who were killed in action or died of wounds during the Great War on a roll of honour.

The cenotaph in Douglas you pass en route to CFB Shilo after coming off Hwy 1 and taking Hwy 340 south has 13 names listed on the plaque of “our glorious dead.”

For some reason, Alex Campbell and James Leith are not among the 53 community members listed who served overseas during the First World War.

The cenotaph — featuring a machine gun on the top used during that war and two verses — also does not list the lone soldier who paid the ultimate sacrifice with his life during the Second World War.

William Brougham is the lone Douglas resident to be killed in action while fighting overseas. He was among 47 who served their country from 1939 to 1945.

During the Boer War from 1899 to 1901, there were four individuals from Douglas who served in South Africa.

Cenotaphs started being unveiled across Canada and in Manitoba communities like Douglas and Wawanesa following the Great War, which started in 1914 and ended on Nov. 11, 1918.

It was the early 1920s for most communities to have a cenotaph erected to remember those from the community who served and died for their country during that four-year war.

Douglas built a simple cairn using boulders and cement, and placed it near the curling club, versus most communities finding a central location in the heart of the hamlet, village, town or city.

The cenotaph became a location where communities could gather Nov. 11 and remember those who died during a Remembrance Day ceremony.

Today, most ceremonies are held indoors because of inclement weather, especially on the Manitoba prairies where it’s periodically a frigid and snowy day.

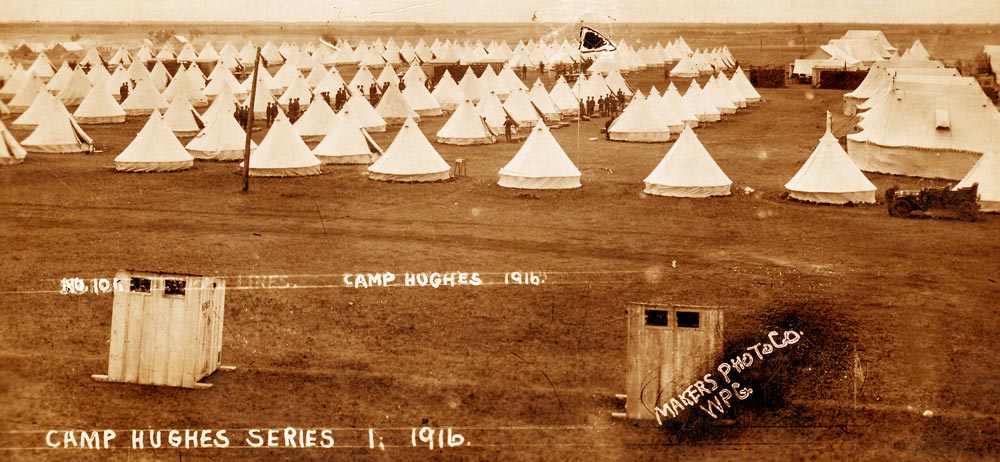

With Douglas located in close proximity to Camp Sewell, later renamed Camp Hughes, soldiers from the community did not have far to go to train before going overseas from Halifax.

It was a train ride east before leaving Nova Scotia by ship across the Atlantic Ocean, landing in England for further training before the trip across the English Channel to France and Belgium.

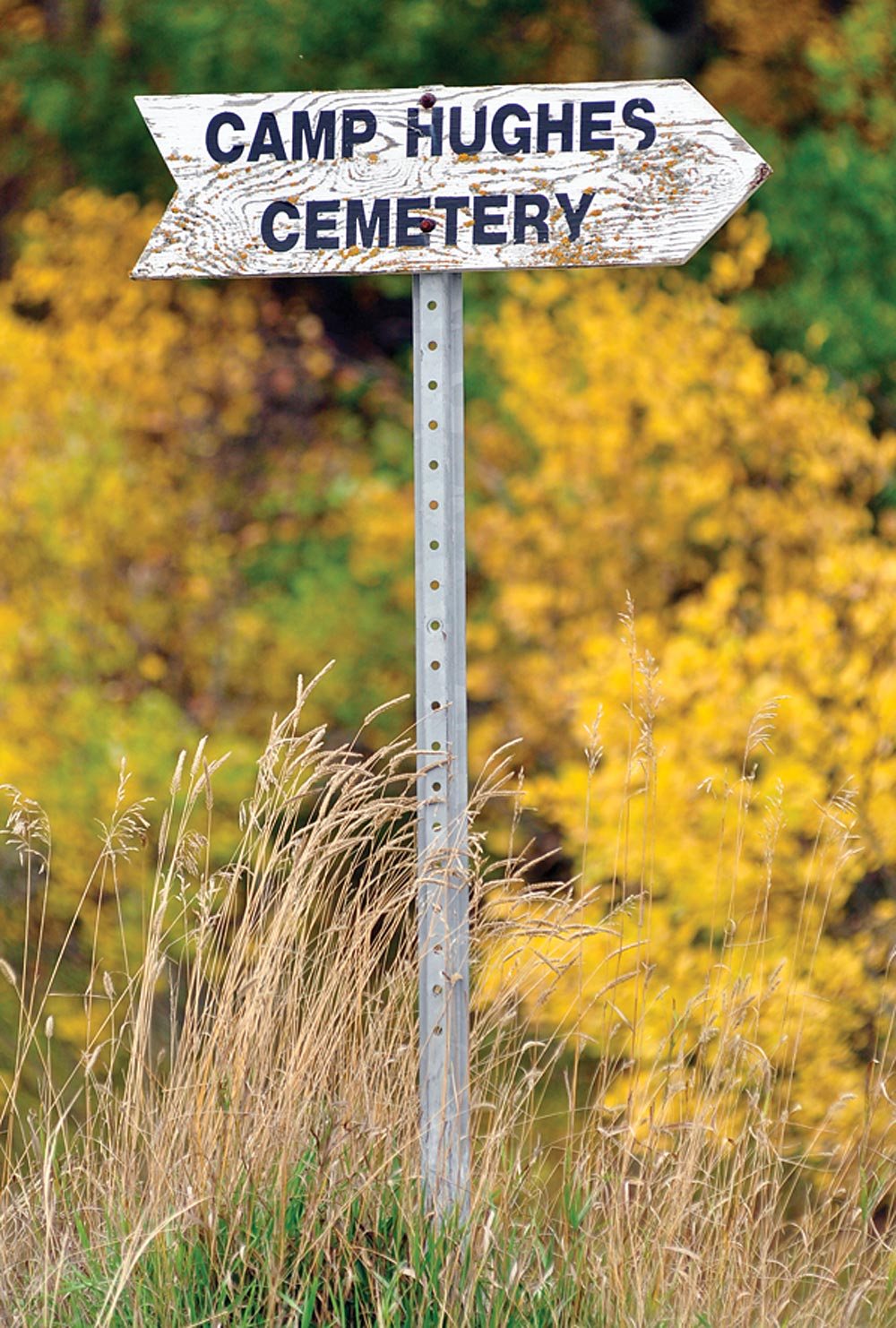

In 1916, the military established a cemetery at Camp Sewell. The remains of six soldiers from the CEF who died while training were laid to rest here. In addition there are 19 civilian graves, including those of several known infants and children of serving soldiers, while five are unknown graves.

An obituary in the Brandon Sun dated July 20, 1916 described the first military funeral to be held at the renamed Camp Hughes. The morning ceremony was for Pte John James Davidson of the 96th Scottish Battalion. He was just 18 on July 13, 1916 when he died from spinal meningitis.

According to the obit, the whole Battalion turned out for Pte Davidson’s funeral, making it a very impressive service. His comrades erected his tombstone.

As part of your tour of Camp Hughes, which is located just east of Carberry, and a few kilometres off Hwy 1 going east, Great War historians or tourists can not only visit the CEF cemetery, but also explore the trench network soldiers used in 1916 and early 1917 in preparation for the Battle of Vimy Ridge in April 1917.

Who are the soldiers buried on the Manitoba prairies where they arrived to learn soldiering before going overseas, but died at the Camp Hughes hospital from sickness to spinal meningitis? No one died as a result of a training injury when soldiers used live rounds and threw live grenades.

Pte Davidson was a farmer in Guernsey, Sask., when the five-foot-nine bachelor enlisted on March 4, 1916 in Saskatoon. Born on Dec. 12, 1897 in Cleobury, England, he was initially hospitalized for 11 days starting on June 6, 1916 with pneumonia. His health worsened and he was re-admitted on July 11.

With his parents notified in Scotland, they chose to have him buried in Canada where he was training at Camp Hughes.

Three days before Pte Davidson’s funeral, fellow soldier Pte John Henry Messenger died from pneumonia, according to his attestation paperwork. He was 24.

Born on Sept. 26, 1891 in Staunton, England, five-foot-two Pte Messenger was a farmer who called Meadow Bank, Sask., home. He enlisted in nearby Wadena on May 3, 1916.

He arrived at Camp Hughes and joined the 214th Battalion. Soon after his training commenced, Pte Messenger was hospitalized on June 23, 1916 with emphysema.

His pay covering July 1 to 17 was $49.70 and was sent to his mother Harriet in Meadow Bank.

Nine days after Pte Davidson died, Pte Arthur Walter Barringer with the 200th Battalion died as a result of alcoholism. He was 43.

Born on Oct. 1, 1872 in Wisconsin, the five-foot-eight American barber twice enlisted to go overseas. He initially enlisted in Regina on Nov. 29, 1915 with the 68th Overseas Battalion. His stint in the Army was short-lived thanks to two different 14-day detentions because of being drunk on duty. Following his second incident, he was discharged for being “undesirable” for CEF service.

So, the Regina barber headed for Winnipeg and enlisted again on April 18, 1916, and was subsequently sent to Camp Hughes with the 200th Battalion. His attestation papers acknowledged he already had three years military experience after serving in the US Army in Florida.

Because the military could not locate next of kin from the United States, the bachelor was buried in the Camp Hughes cemetery alongside two other comrades at the time.

There’s no information in the Canadian military archives on the next soldier to die at Camp Hughes. Because of his age he was “rejected” as a CEF volunteer. A member of the Canadian Military Police Corps (CMPC), Pte William Perkins was 48 when he died of sickness on July 26, 1916. He was with the No. 10 Detachment of the Winnipeg-based 10th Battalion CEF.

At the outset of the First World War, the Canadian Army consisted of a tiny “Permanent Force” or Regular Army and a large non-permanent Militia.

There was no organized Corps or Regiment of Military Police in the Army, while a few units had a Regimental Police or Provost section consisting of a dozen or so men under the command of a Provost Sergeant.

Places like Camp Hughes and Garrisons had locally appointed personnel functioning as Military Police, however ,discipline was primarily a Regimental concern, through the normal chain of command.

Soldiers temporarily assigned to Military Police duties were expected to be locally recruited, often from gentlemen of large physical stature, who might or might not have civil police experience. MGen William Otter’s The Guide: A Manual for the Canadian Militia describes very briefly, the duties and identification of military police. Generally, the duties of Camp Police were to maintain order, regulate civilian tradesmen, provide escorts for defaulters and enforce sanitary regulations.

In September 1914, a small detachment of MPs accompanied the first contingent of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) to England. After arriving in England, the detachment underwent training with the British Military Police. During the First World War, Canadian Military Police appear to have adopted British methods, organization and equipment.

Unfortunately, detailed records of this period were lost due to a fire in 1917.

Pte Percy Douglas Smith was the fifth soldier to be buried at Camp Hughes following his death on Aug. 15, 1916 from sickness. He was 30. His family provided his grave marker.

A jeweller from Shoal Lake, he enlisted in his hometown on Jan. 8, 1916 and was placed with 226th Battalion. Standing five-foot-nine and another bachelor, Pte Smith was born on April 8, 1895 in Westchester, Nova Scotia.

The last military burial in Camp Hughes before the training shifted to Camp Shilo before the Second World War, and the training area was closed, happened soon after LCpl John James Kendal of the 188th Battalion died on Sept. 12, 1916 of erysipelas. He was 31.

Born in Bradford, England on Oct. 20, 1884, LCpl Kendall was a clerk from Melfort, Sask., when he enlisted on Feb. 15, 1916. The five-foot-eight bachelor was sent to the Camp Hughes hospital on June 8, 1916 suffering from a sore hip.

There were no medical documents in his now digitized military records why his sore hip in the summer of ‘16 led to erysipelas, which is an infection of the upper layers of the skin (superficial).

The most common cause is group A streptococcal bacteria. Erysipelas results in a fiery red rash with raised edges which can easily be distinguished from the skin around it.

Erysipelas can be serious but rarely fatal. It has a rapid and favourable response to antibiotics, but remember this was 1916 and did medical staff have antibiotics to treat what started out as fiery red rash?

With the Melfort platoon at Camp Hughes, LCpl Kendall’s grave marker was erected by his comrades. The inscribed on his stone “This day the noise of batle (sic) the next victors song.”

The grave markers for Pte Messenger, Pte Barringer and Pte Perkins were installed by Veterans Affairs.