Stag Special

Historical, genealogical, anthropological, archaeological and DNA analysis has been used to identify another Canadian Great War soldier.

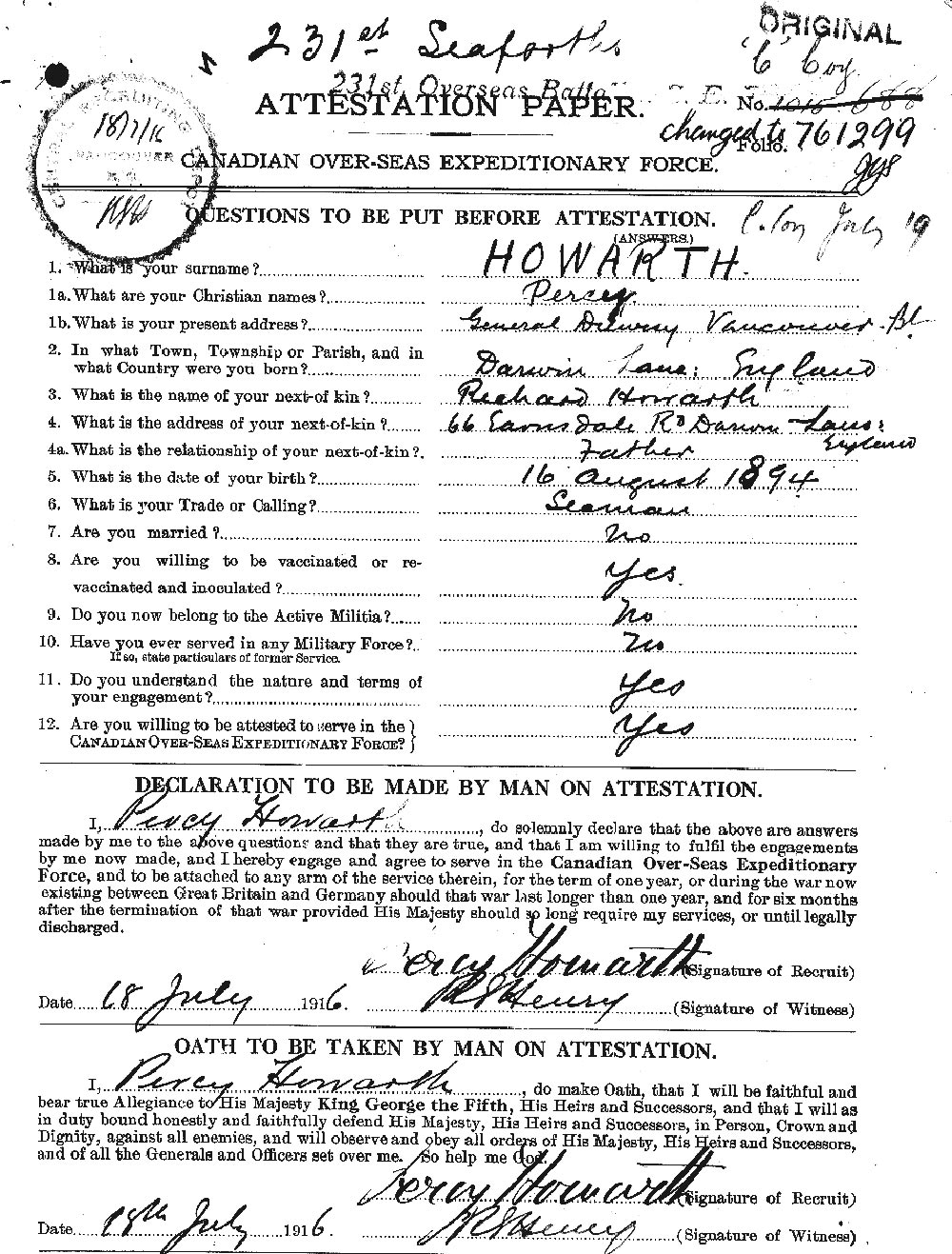

The Department of National Defence (DND) and the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) have confirmed remains recovered in Vendin-le-Vieil, France, are those of First World War soldier Cpl Percy Howarth.

Cpl Howarth was born on Aug. 16, 1894, in Darwen, Lancashire, England, one of eight children of Richard and Margaret Howarth (née Dearden).

He immigrated to Canada in 1912, sailing from England on RMS Victorian, and worked as a sailor in Vancouver before enlisting with the 121st ‘Overseas’ Battalion, Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF), at the age of 21. On Aug. 14, 1916, he sailed from Halifax aboard SS Empress of Britain arriving in Liverpool on Aug. 24. Four days later, he joined the 7th Canadian Infantry Battalion.

After training in England, he was sent to France on Nov. 29 and was promoted to the rank of lance corporal and then corporal on May 14, 1917. While in France, Pte Howarth got sick with influenza and spent a week in hospital.

Cpl Howarth fought with the 7th Canadian Infantry Battalion, CEF, in the Battle of Hill 70 near Lens, France, which began on Aug. 15, 1917. The 23-year-old was reported missing, then was later presumed to have died on that day.

“Time and distance do not diminish the courage Cpl Howarth brought to the battlefield in service to Canada,” said Minister of National Defence Anita Anand. “His family should trust that I and all Canadians will remember the ultimate sacrifice he made. Lest we forget.”

Added Minister of Veterans Affairs and Associate Minister of National Defence Lawrence MacAulay, “Nearly 10,000 Canadians were killed, wounded or declared missing in the Battle of Hill 70, Cpl Howarth among them. Now, more than 100 years later we remember Cpl Howarth’s selfless courage and sacrifice in the name of duty and that of all his comrades.”

The Battle of Hill 70 came after the success Canadians had during the Battle of Vimy Ridge, which started at 5:30 a.m. on April 9, 1917, and ended with the capture of the ridge by Canadians on April 12.

Cpl Howarth and the 7th Battalion was on the left flank of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Brigade and took part in the second wave of the attack between the Blue and the Red Line objectives. The fight for the Red Line was difficult as the Germans held strong in their position. Heavy casualties were reported from this attack.

The 7th Battalion then pressed towards the Green Line objective. However, they had to withdraw to the area of the Red Line since their left flank was exposed. During the afternoon of Aug. 15, the 10th Canadian Infantry Battalion was brought forward to help the 7th Battalion hold the line against German counter-attacks.

On Aug. 16, a second attack led by the 10th Battalion with support by the 7th Battalion, captured the Green Line. From Aug. 15 to 18, 1917, the 7th Battalion suffered 118 casualties with no known graves in connection with the assault on Hill 70.

The capture of Hill 70 in France was an important Canadian victory during the First World War, and the first major action fought by the Canadian Corps under a Canadian commander. The battle, in August 1917, gave the Allied forces a crucial strategic position overlooking the occupied city of Lens.

The Battle of Hill 70 exacted a heavy toll during 10 days of fighting, with more than 10,000 Canadians killed, wounded or missing, including more than 1,300 with no known grave. More than 140 men of the 7th Canadian Infantry Battalion were killed, 118 of whom were missing with no known grave.

LGen Arthur Currie took command of the Canadian Corps in June 1917, following the Corps’ victory at Vimy Ridge. Replacing British Gen Julian Byng, LGen Currie was the first Canadian put in charge of the Corps, Canada’s main fighting force on the Western Front.

In July, LGen Currie received orders from Gen Douglas Haig, commander-in-chief of all British-led forces in western Europe, to capture the French coal-mining city of Lens. Gen Haig hoped this action would divert German attention and military resources away from the major Allied offensive then raging at Passchendaele, in Belgium.

Lens, which lay inside German-occupied territory not far from Vimy Ridge, had suffered terribly in the war. The Canadians were sent to capture a city that lay half in ruins. LGen LGen Currie thought that Hill 70 — an elevation on the outskirts of Lens, so named because it was 70 metres above sea level — was tactically more important.

He believed a traditional, frontal assault on Lens, followed by an Allied occupation of the city, would be futile if the Germans could simply shoot down at the Canadians from the commanding hills. So LGen Currie convinced his superiors, including Gen Haig, to drastically alter the plan of attack, by making Hill 70 the Canadians’ main objective.

LGen Currie believed that by capturing the hill he could aggravate the Germans in surrounding positions and provoke them to come out of their dugouts and attack. The Canadians could then kill large numbers of the enemy and drive them out of the area.

Throughout late July and early August, as the Canadians prepared to assault Hill 70, they harassed and distracted the German forces. Hill 70 was a treeless elevation which dominated Lens. The city itself had been bashed by years of warfare, and German trenches cut through the ruins of the brick homes of the city’s coal miners. The ruins offered plenty of cover for the Germans in the city.

The Canadian Corps launched its bid for Hill 70 at 4:25 a.m. on Aug. 15, 1917. The Royal Engineers fired drums of burning oil into the German positions on the hill, along with heavy artillery fire.

The Germans of the 7th Infantry Division saw the attack coming and were ready with defensive fire. Still, by 6 a.m., the Canadian infantry — shielded by the smoke screen of the burning oil — had captured several of its early goals.

German resistance stiffened as the Canadians advanced on the hill. The smoke screen drifted away and German machine guns and rifles killed and wounded many attacking Canadians. Attacking Allied soldiers now ran from shell hole to shell hole as they tried to move forward up the hill.

Slowly, the Canadians captured German machine-gun posts and advanced up the hill. Meanwhile, LGen Currie ordered 200 gas bombs fired into German positions south of Lens, as a diversionary tactic during the actual assault on Hill 70.

The German forces counter-attacked before 9 a.m. the next day, but the Allies broke each enemy attempt to reclaim ground. A second wave of afternoon counter-attacks was also rebuffed. German infantry troops were met by “fountains of earth sent up by the heavy shells” and “a hail of shrapnel and machine-gun bullets,” according to the history of the German 5th Foot Guard Regiment, and were annihilated.

The Canadians eventually captured the heights of Hill 70, but the cost was high. By the end of only the first day, 1,056 Canadians were dead, 2,432 were wounded and 39 had been taken prisoner. It’s not known how many Germans died that day.

Fighting continued around Hill 70 through Aug. 18, with the Canadian Corps withstanding continued German resistance and counter attacks, in localized fighting which included mustard gas and flamethrowers. After four days of hard combat, the Canadians turned back 21 German counter-attacks and held on to their new positions atop Hill 70. About 9,000 Canadians were killed or wounded in the overall battle, while an estimated 25,000 Germans were killed or wounded.

The fighting at Hill 70, overshadowed by the more famous Canadian battles at Vimy Ridge in April 1917 and at Passchendaele in the fall of that year, is not as well known to many Canadians. However, some historians argue Hill 70 was one of Canada’s most significant contributions of the First World War, more important even than Vimy Ridge.

“It was altogether the hardest battle in which the Corps has participated,” wrote LGen Currie himself. “It was a great and wonderful victory. [General Headquarters] regard it as one of the finest performances of the war.”

Thanks largely to LGen Currie’s tactical skill and prowess, the battle resulted in a German defeat and the diversion of German resources and attention away from the larger Allied campaign underway at the time at Passchendaele. This success, coming after the victory at Vimy, further boosted Canada’s sense of pride and nationhood on the world stage.

Most importantly, it cemented the reputation of the Canadian Corps as an effective assault force within the larger British army — a reputation the Canadians would prove again and again, under Currie’s leadership, through the remainder of 1917 and 1918 as the war eventually wound to an end.

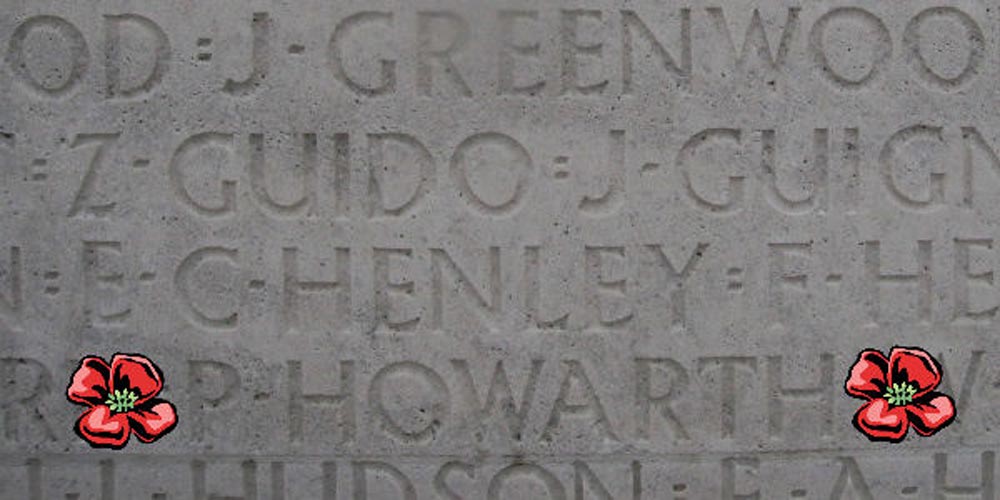

Canada’s sacrifices — including the nearly 1,900 Canadian soldiers who died in the battle — are remembered today at the Hill 70 Memorial, and at the Loos British Cemetery outside Lens, France. The names of Canadians who died at Hill 70 with no known graves are also inscribed on the larger memorial at Vimy Ridge.

The family of Cpl Howarth have been notified and the CAF is providing them with ongoing support. He will be buried at the earliest opportunity in the Commonwealth War Graves Commission’s Loos British Cemetery in Loos-en-Gohelle, France.

Quick Facts

• After the war, Corporal Howarth’s name was engraved on the Canadian National Vimy Memorial, which commemorates Canadian soldiers who died during the First World War who have no known grave.

• On June 9, 2011, human remains were discovered during a munitions clearing process for a construction site in Vendin-le-Vieil, France. Alongside the remains were a few artifacts including a digging tool, a whistle and a pocket watch.

• Through historical, genealogical, anthropological, archaeological, and DNA analysis, and with the assistance of the Canadian Forces Forensic Odontology Response Team and the Canadian Museum of History, the Casualty Identification Review Board was able to confirm the identity of the remains as those of Cpl Howarth in October 2021.

• The Canadian Armed Forces Casualty Identification Program, within the Directorate of History and Heritage, identifies unknown Canadian service members when their remains are recovered, and provides them with a respectful burial in an appropriate cemetery. The program also identifies service members previously buried as unknown soldiers when there is historical and archival evidence confirming the identification. In such cases, a new headstone is engraved with their name and the member is officially identified and commemorated by the CAF.

• The Commonwealth War Graves Commission commemorates the 1.7-million Commonwealth servicemen and women who died during the two world wars. Using an extensive archive, the Commission works with its partners to recover, investigate, and identify those with no known grave, in order to give them the dignity of burial and the commemoration they deserve.

• Did you know? Lt Lancelot Joseph Bertrand was among the thousands of soldiers who died during the Battle for Hill 70. Born in Grenada, Bertrand became one of the first Black volunteers in the CEF when he enlisted in September 1914 at Valcartier. He was a private in the 7th Battalion when he fought at the Second Battle of Ypres (April to May 1915) and the Battle of Festubert (May 1915), where he was wounded. He was promoted to sergeant in 1916 and then to lieutenant, one of only seven Black officers in the CEF. Lt Bertrand received a Military Cross for his actions in the Battle of Vimy Ridge (April 1917). He was killed on Aug. 15, 1917 during the Battle for Hill 70.

• Six Victoria Crosses — the lives of many Canadian soldiers were saved by the work of Pte Michael O’Rourke, an Irish-born Canadian stretcher bearer. He received a Victoria Cross for repeatedly running into German fire to rescue wounded Canadians. Maj Okill Massey Learmonth of Québec jumped atop a parapet and hurled hand grenades at the enemy during a German counter attack on Aug. 18. The 23-year-old officer caught German grenades which were thrown at him, and tossed them back at the enemy. He was wounded and later died, and was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross. Another four Canadians received the Victoria Cross for bravery at Hill 70, the British Empire’s highest award for military valour: Pte Harry Brown, Sgt Frederick Hobson, CSM Robert Hill Hanna and Cpl Filip Konowal.

• • •

https://canadiangreatwarproject.com/person.php?pid=48590

https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/military-heritage/first-world-war/personnel-records/Pages/item.aspx?IdNumber=471296

A badly wounded Canadian soldier drinks his hot coffee at a soup kitchen located 100 yards from German lines, amid the push on Hill 70 in August 1917 during the Great War. Photos Dept National Defence/Library and Archives Canada

Canadian soldiers take a break in August 1917 while resting in a captured German trench on Hill 70 in France during Great War.

Pte Michael J. O’Rourke of the 7th Canadian Infantry Battalion was awarded a Victoria Cross medal while serving as a stretcher-bearer during the fighting for Hill 70 in August 1917. He had already receiving the Military Medal for heroism during the Battle of the Somme in 1916. Here, in this portrait he wears the ribbons for both medals.

In September 1917, Gen Arthur Currie and other Canadian Corps commanders attend a memorial service to men who fell at the Battle of Hill 70 during the First World War.

A watch and whistle were found with the remains of Cpl Percy Howarth. Both were later restored by CWGC’s Christian Cousin. Photos CWGC