Pte Bill May and his brother Harold spent many months honing their infantry skills at Camp Hughes before going overseas to be part of the Battle of Vimy Ridge in April 1917. During his military training, Pte May wrote many postcards which he sent to family in the Binscarth area. While brother Harold was seriously wounded in France, brother Bill returned home and later spent time at Camp Shilo working at the YMCA, while also running the theatre at what is now L25. Pte Bill Minary also liked using his camera of that era, and those images are kept in the many scrapbooks he compiled and passed on to his grand-kids.

Jules Xavier

Shilo Stag

A veteran of the Battle of Vimy Ridge more than a century ago left his descendants a treasure trove of black and white photographs and memories he kept in scrapbooks.

Using his trusty Kodak film camera, Bill May took photos at the now defunct Camp Hughes when it was a hive of activity as Canadian soldiers trained on the prairies before heading overseas as members of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) during the Great War.

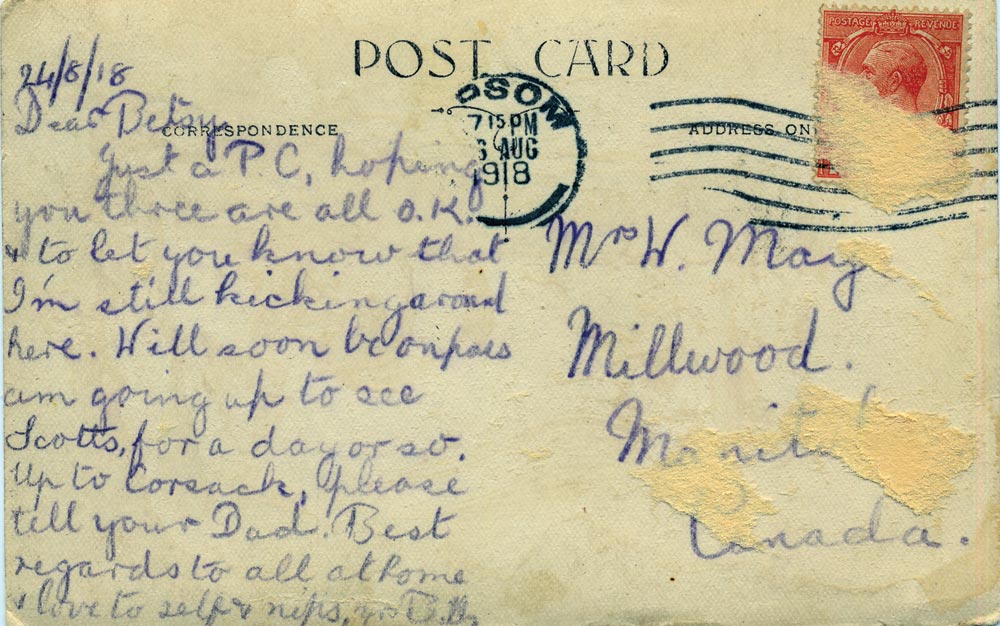

Each photograph tells a story as best Pte May could compose with the camera equipment of that era. Once printed off — usually in a postcard format where you could mail it after writing on the back, and placing a two cent stamp featuring King George V on it — he added to his First World War scrapbook.

One book called One Man’s Memories of WWI, May left remarks or identification of individuals he served with alongside the photo, or on the back. The scrapbooks also include postcards he sent home to the family farm in Millwood, the words scrawled in pencil or ink, that soldiers could purchase at Camp Hughes. These cards were taken by photographers working with Advance Fotos out of Winnipeg, or at the time Camp Sewell before it was renamed after MGen Sir Sam Hughes.

As you turn the pages it’s like going back in time as you look into the faces of soldiers long gone, whether they died on the battlefields of Belgium or France, or returned home to raise a family and die as grandfathers on Canadian soil.

Like May, who died on Aug. 8, 1974 in Binscarth where he retired after leaving CFB Shilo. He was 82.

“He was meticulous in how he kept his scrapbooks,” said grand-daughter Kathleen Mowbray (nee Schrot) of Minnedosa. “[Aunt] Margaret has held on to a lot of the scrapbooks, and photos, from her dad, and we’re now starting to share them with other family members.”

Brother Kelvin Schrot thought it would be nice to share his grandfather’s story with the Stag to coincide with Remembrance Day.

“I’ve learned things about my family I did not know since [the Stag] started looking at my grandfather’s life, from being in the Army to working on this Base for all those years,” he said.

Born on April 8, 1892 in London, England to a family of eight brothers and a sister, Bill May was one of the first employees hired at Camp Shilo by the YMCA in 1940.

With his brother Harold, they arrived in Manitoba after their journey across the Atlantic Ocean brought them to Canada. With the advent of the First World War, May first married Grace Murdoch and started a family.

Brother Harold enlisted first, with the Winnipeg Rifles, and began training at Camp Sewell. In a postcard letter sent to his brother written on July 23, 1915, he wrote: “You got the [address] all right, but you did not put ‘Man’ [Manitoba] on it and it went way down to Montreal. What do you think of the picture taken outside the tent?”

The postcard shows seven soldiers, including Harold, standing in front of military-issued scratchy wool blankets on the ground outside of their tent.

May would join his brother at the renamed Camp Hughes that same year as Canada prepared its soldiers for overseas, including the Battle of Vimy Ridge in 1916 that was being planned for April 1917. Both served with the 61st and 44th Battalions, the latter part of the scout section.

Writing postcard letters was the norm for May after he arrived overseas, with brother Harold and him posing for photos to send home to his wife “Betsy”. In one written on Dec. 7, 1916, he wrote: “Just received three letters from you, written in Oct and 3rd Nov, a little late but nevertheless very welcome, will write as soon as possible in the meantime what do you think of your old pal, notice the aggressive attitude the same old ready for a row look eh, well dearest old girl hope you are all in the best of health and spirits, and that you have … time at Xmas. I am glad you got the photos.”

The photo in question on the front of the postcard has Bill May standing with a cigarette in his right hand, his brother Harold in a fur coat and a cigarette in his left hand, with a seated comrade wearing an army long coat.

Besides serving in the Battle of the Somme, both brothers fought at the Battle of Vimy Ridge, where Bill was wounded in the leg by shrapnel, while Harold received a nasty blow to his cheek, chin and shoulder after a bomb went off near him. According to Mowbray, he was passed over when the medics came for the wounded, thinking his wounds were mortal.

“Three days later, he was found in the mud alive,” she recalled. “He was taken to the hospital and was one of the first recipients of reconstructive surgery. [Harold’s] zest for life remained until his death [on Nov. 10] in 1951.”

May would recuperate from his war wound in the “massage department’ of the military convalescent hospital at Woodcote Park, Epsom.

In a letter he wrote home, dated Aug. 8, 1918, there was not much information shared about his wound with wife “Betsy” as he recuperated: “… let you know I’m still kicking around here. Will soon be on [leave] pass am going up to see Scotts for a day or so. Up to Corsock.”

May was referring to his road trip to the Village of Corsock in Scotland while he recovered from his shrapnel wound.

Following the war, after returning to the family farm, May would raise a family of seven, including three sons who all enlisted in the Second World War. Son Harold, 23, was KIA in Holland on Feb. 8, 1945. Eldest son Walter died in 1971 after saving a co-worker’s life.

After moving to Camp Shilo, his remaining sons worked the farm, while daughters Margaret, Joyce and Dorothy joined their parents in the new PMQs being built for military families after 1947.

In charge of the YMCA, May helped the soldiers training for the Second World War with movies, library, sports equipment, canteen service and the Legion. During this time, Camp Shilo also housed German POWs — they were tasked with cleaning on the army training base.

May’s children attended the first Shilo school, with dad a member of the school committee. Enrolment that first day was 16. By 1948, enrolment was up to 130. Daughter Margaret was among the first Grade 12 graduates.

After the war, according to Mowbray, Maple Leaf Services hired her grandfather to manage the Ubique Theatre — now L25 — in 1946. Besides the projectionist, he was also the Base’s Justice of the Peace starting in 1952.

Retiring on Oct. 12, 1961, and moving to Binscarth, May never slowed down. Mowbray said her grandfather was thrifty, and never owned a car. On the Base he would walk or ride his bicycle. If he needed a car, he had friends who would lend one.

During Canada’s centennial in 1967, May received the Order of the Crocus “in grateful recognition of this contribution to the welfare and development of Canada.”

“It’s a wonderful acknowledgement of what my grandfather did for his country, serving in the [Great War] and helping soldiers at Camp Shilo who were going off to fight another war,” said Mowbray.

May’s grandkids Kelvin and Kathleen said May was not one to share stories of the carnage from the Great War battlefields where he fought, but on occasion if he was sharing war stories with old comrades, if they listened intently they might hear something he did not readily share with the family.

• • •

The need for a central training camp in Military District 10 (Manitoba and Northwest Ontario) resulted in the establishment of Camp Sewell in 1910, on Crown and Hudson’s Bay Company land near Carberry. The site was accessible by both the Canadian Northern and Canadian Pacific Railways and the ground was deemed suitable for the training of artillery, cavalry, and infantry units.

The first summer training camp, in 1910, was attended by 1,469 soldiers. Militia soldiers continued to train in the summers up until the final pre-war camp in July 1914.

After the formation of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) in ’14, the camp was expanded to train the large numbers of new recruits. A year later, 10,994 men of all ranks attended camp, including Pte Bill May’s brother Pte Harold “Polly” May.

Permanent buildings were constructed, a rifle range with 500 targets was set up, and the water supply was improved.

In September 1915, Camp Sewell was renamed Camp Hughes in honour of Canada’s Minister of Militia and Defence, MGen Sam Hughes.

In 1916, the camp was home to 27,754 troops who trained on the wind-swept prairie grounds, including Pte Bill “Ning” May, making it the largest community in Manitoba outside of Winnipeg.

Construction reached its zenith, and the camp boasted six movie theatres, numerous retail stores, a hospital, large heated in-ground swimming pool, Ordnance and Service Corps buildings, photo studios, post office, prison and many other structures.

The May brothers and their fellow troops were accommodated in neat groups of white bell tents, located around the central camp.

Camp Hughes’ trench system was developed in 1916 to teach trainee soldiers like the May brothers the lessons of trench warfare which had been learned through great sacrifice on the battlefields of France and Flanders.

Veteran soldiers were brought back to Canada to instruct in the latest techniques based on what they had experienced first-hand facing the Germans. The trenches accurately replicated the scale and living arrangements for a battalion of 1,000 men.

The battalion in training would enter the system, after first being issued their food, ammunition and extra equipment, through two long communication trenches which led up to a line of support and front-line trenches. All along the route dugouts with thick earth overhead cover housed the troops and protected them from artillery fire.

Once established, the battalion would undergo training which included: daily routine, sentries, listening posts, trench clearing, and finally, a frontal assault on the “enemy” by going over the top and across no-man’s land into the enemy line of trenches.

The shallow “enemy” trenches were built on higher ground as were most of the German positions on the Western Front in Europe.

An additional trench system served as a “grenade school.” Here, troops would practice working their way down an enemy occupied trench and finally throw live grenades from the trench into pits dug near the end.

Though much eroded after more than a century, the trench system is still essentially intact and is the only First World War training trench system in North America.

A decline in voluntary enlistments — culminating in the Conscription Act — caused the suspension of training in 1917 and 1918. The grounds also includes a small graveyard where a few soldiers are buried, while soldiers who might have trained in nearby Brandon at another military establishment and died before going overseas, are in the municipal cemetery.