Jules Xavier

Shilo Stag

Standing over the grave of his great-grandfather Charles Sharp, then Maj Reg Sharpe shed a few tears as he reflected on what the 22-year-old endured during the Great War when he was on the battlefield a century ago.

“It was an emotional experience to set foot in any Commonwealth cemetery, but when you have a direct connection to yourself there … you don’t know what to say,” recalls Sharpe, who ran the Base CE section — now RPOU-W Det Shilo — from 2011 to 2013. “Looking over his grave, I was reflecting on what he must have gone through in that war.”

He added, “It was windy, a light drizzle was coming down. To think here’s my great-grandfather buried so far away from home. I thought to myself, what might he have been thinking as he lay alongside the cemetery on the night of Aug. 16, 1917 bleeding from multiple gun shot wounds, knowing he was dying, as he watched the burial parties digging his grave.

“Was he thinking of the woman [Annie Hawkins of Stephenville Crossing] who would have been his wife when he returned home from the war, or the son [Charles Sharpe born on Oct. 25, 1916] he’d never see? That was a touching moment for me, especially when you look at the care that goes into these [Commonwealth] cemeteries.”

Now LCol Sharpe and his wife Kim went on a second honeymoon to France, and used the opportunity to finally visit his great-grandfather’s First World War grave near Poeperinghe, Belgium. After his death on Aug. 17, 1917, the private with the Royal Newfoundland Regiment’s 1st Battalion was interred in what is now the Dozinghem British Military Cemetery.

“The cemetery was only about a 100 miles from where we were staying in Paris [France], so we made plans to visit that cemetery and others while we were overseas,” he recalls.

“It was 2004, and it was disturbing to me that in 87 years no family had gone overseas to visit the grave. I have been thinking about it a lot since I learned I had a relative die in the First World War.”

Born in Hearts Delight, Charles Sharp was the son of George and Margaret Sharp of Trinity Bay, Newfoundland. He is commemorated on page 112 of the Newfoundland Book of Remembrance. It was this book which started Sharpe’s search for his great-grandfather after he obtained his military records in 2001. The files proved fruitful, and answered some of his unanswered questions put to other family members.

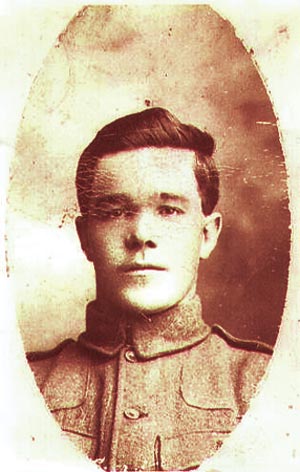

A photo of the man which hung on his grandfather’s wall was LCol Sharpe’s early exposure to a young soldier who left his “railroading” job to be part of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) when the Great War was a few years old after war started on July 28, 1914.

“I would see that photo at my grandfather’s house, and when I was growing up I thought he had disappeared into the abyss,” says LCol Sharpe. “I wanted to know more about him, but no one would talk about it.”

The reason for this he would learn years later while researching his great-grandfather’s legacy as a soldier who made the supreme sacrifice for King and Country.

“I was doing a paper when I was at university and decided to look him up in the Book of Remembrance for Newfoundland,” he says. “I knew he was a Sharp without the ‘e’ which was later added by my grandfather, and that he died on Aug. 17 in 1917. I was discussing it with my father [Reg Sr., a CAF soldier at CFB Gagetown] and he told me his first name was Charles.”

With this knowledge, he found him in the book and used the name and date of death to confirm he found his great-grandfather.

He also used another soldier, 22-year-old Pte John Simms, who died on the same battlefield, and a fellow Newfoundlander, to track his great-grandfather’s final days in the Great War. He also researched the data base on the Canadian virtual memorial website.

“I did not know what to expect when I was doing my research,” he says. “I was told he just disappeared in a swamp.”

Much to his surprise, it was surreal when the website provided LCol Sharpe with a grave number, and cemetery where Pte Sharp was interred.

“This became personal for me, a journey for me to discover my family heritage despite the passage of time. I think about him, and what I have today, and why I have it, because a blood relative paid the ultimate sacrifice for our freedom.”

LCol Sharpe discovered there were 19 men from Newfoundland buried in the same cemetery as his great-grandfather.

“These men went to war, like my great-grandfather, to make a better life for their families,” he says. “He left Newfoundland on June 16, 1916 on the steamship SS Sicilian to replenish the soldiers who had died in all the Sommes battles.”

Having enlisted in St. John’s on April 4, 1916, two months shy of his 21st birthday, the five-foot-eight Pte Sharp arrived in Southampton, England after crossing the Atlantic Ocean.

LCol Sharpe’s great-grandfather would be wounded twice after arriving in Rouen, France, then joining the First Battalion on Oct. 14, 1916 and fighting the Germans in the muddy trenches.

His first battle wound occurred on Jan. 29, 1917. He then contracted the flu in Amiens on Feb. 17. After recovery, he returned to the Front and was wounded a second time during the Battle of Arras on April 11. The third time would prove fatal when he was wounded on Aug. 16 near Steenbeck. The following day he was dead, his body strafed by machine gun fire in the chest, and right arm and leg.

“He died in a casualty clearing station,” says LCol Sharpe. “Doing my research I also learned Pte Simms died on the same day, and when I arrived at the cemetery in Belgium, found him buried beside my great-grandfather.”

It was a costly battle for the Newfoundlanders, though 16 men received decorations. Seventy-nine men were reported killed, 340 wounded and 43 missing. Back home in Hearts Content, George Sharp would receive a telegraph on Aug. 25 informing him of his son’s death.

The telegram read: “Regret to inform you Record Office, London, today reports No. 2417, Private Charles Sharp, died as a result of gunshot wounds in chest, right leg and right arm, at Casualty Clearing Station, on August seventeenth.”

It was signed by R.A. Squires, the Colonial secretary. There was a note to the telegraph operator appended: “This message is not to be sent until receiving office notifies that message to Rev. F. Smart has been delivered and acted upon.”

The files in LCol Sharpe’s possession also exposed his great-grandfather’s penchant for missing parades as he began his military training.

Late for an Aug. 8, 1916 8:45 a.m. parade, Pte Sharp was punished with “three days C.B.” He earned another day of punishment on Sept. 17, 1916 for being absent from a church parade. He had to forfeit a days pay two days later — he was paid the equivalent of 50 cents per day — for being absent from a defaulters parade scheduled from 6 to 9:30 p.m. Overseas, in France, on Oct. 5, 1916, he lost two days pay for “being deficient of kit.”

Pte Sharp would lose his life during the Battle of Langemarck — Aug. 16 to 18, 1917 — which was the second Allied general attack of the Third Battle of Ypres on the Western Front near the Steenbeek River.

Here’s what Pte Sharp and his fellow Newfoundlanders had to to endure, according to records:

“The advance started from the bank of the Steenbeek River in the early dawning. For the first 500 yards progress was necessarily slow, and made under most difficult circumstances. The ground has been characterized as a ‘floating swamp,’ and the term will probably convey as accurate an idea as can be given of the actual conditions of the ground. As the men waded through the swamp some sank to their waist and others deeper, in many cases having to remain there until pulled out by more fortunate ones. Unfortunately, there was little or no time in which to aid a comrade who had sunk into the swamp. The advance was preceded by a sweeping barrage, and those who could keep themselves above the surface had to keep pace with the barrage, otherwise its effectiveness would be lost. One favourable circumstance of the advance, however, was the lack of fighting spirit in the German troops who defended the position.”

The British Empire’s objective for the Battle of Ypres and use of soldiers from the Newfoundland Battalion in 1917 was to capture the Belgium coast. Like Sharp, Pte Simms of Fogo received serious wounds to his head and right leg on Aug. 16, 1917 and died the next day. The fisherman was awarded the Military Medal (MM) for bravery for his actions on the swampy battlefield, rescuing men and using his Lewis Gun to inflict casualties on the German side.

LCol Sharpe says his grandfather’s mother, Annie Hawkins, would not learn about the death until a month later, and it was not from Pte Sharp’s father.

“The letters and cards from Europe which had arrived with regularity, suddenly stopped arriving … she feared the worst,” he says.

The widow would not see a penny of Sharp’s military pay, with his father writing letters to secure it. This caused a rift in the family, according to Sharpe, which was never mended. When he was of age, Charles Hawkins took on his late father’s last name, and added the ‘e’ to it. He would go on to have 16 of his own kids.

“What is unfortunate for Annie and that time when you were not married, my great-great-grandfather was only worried abut his son’s military pay, not that of his grandson or her,” says LCol Sharpe.

While Simms had $26.18 in his Bank of Montreal account based on his military pay, Sharp’s father was awarded the $95.38 his son had banked.

“As the promised wife,” Hawkins wrote a letter dated Sept. 11, 1917 asking the Minister of Justice for all, or for a share of Pte Sharp’s military pay.

“It’s over two years I have been betrothed to him,” she wrote, adding “[Charles] promising to marry me when he returned from the war.”

Hawkins was not looking for the money for herself, but for Pte Sharp’s son. She even offered the letters and cards they wrote to each other as evidence of their love, and marriage promises, but ultimately the money went to the father. He received it on July 3, 1918.

“Because of what he did, part of our family history is lost,” says LCol Sharpe.

Despite the tragedy and family politics of that time, he is still proud of his great-grandfather’s contribution to the Great War, and his and his own father’s contribution to the CAF, including a posting to CFB Shilo.

LCol Sharpe always stands stoically, and salutes proudly during the annual Remembrance Day ceremonies he attends, from his days at CFB Shilo, to when he was posted to Garrison Edmonton, and this posting season he’s off to CFB Gagetown after a one-year stint in Ottawa. It’s always a poignant moment as he also reflects on his great-grandfather’s sacrifice during the Great War.

Lest we forget!

Then Maj Reg Sharpe stands at the grave of his great-grandfather Pte Charles Sharp, who was killed in action (KIA) on Aug. 17, 1917, in a military cemetery in Belgium. Photos submitted

Then Maj Reg Sharpe discovered his great-grandfather was buried in Belgium near the battlefield where he sustained serious machinegun wounds. He was buried next to fellow Newfoundlander Pte John Simms, who was wounded and died on the same day as Sharp. Simms was awarded the Military Medal for his bravery and actions facing the Germans with the Lewis Gun company he commanded during the Battle of Langemarck in August 1917.

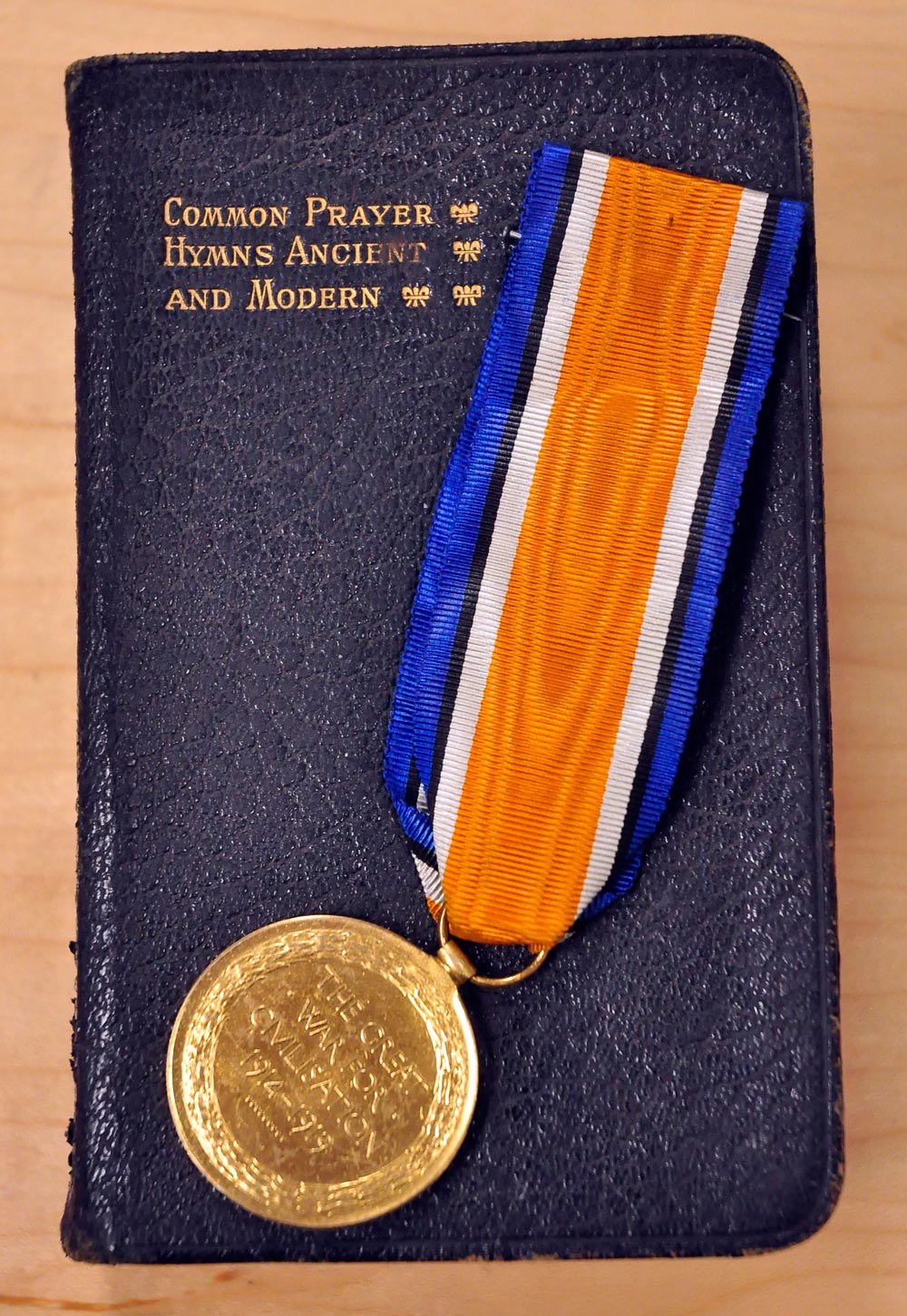

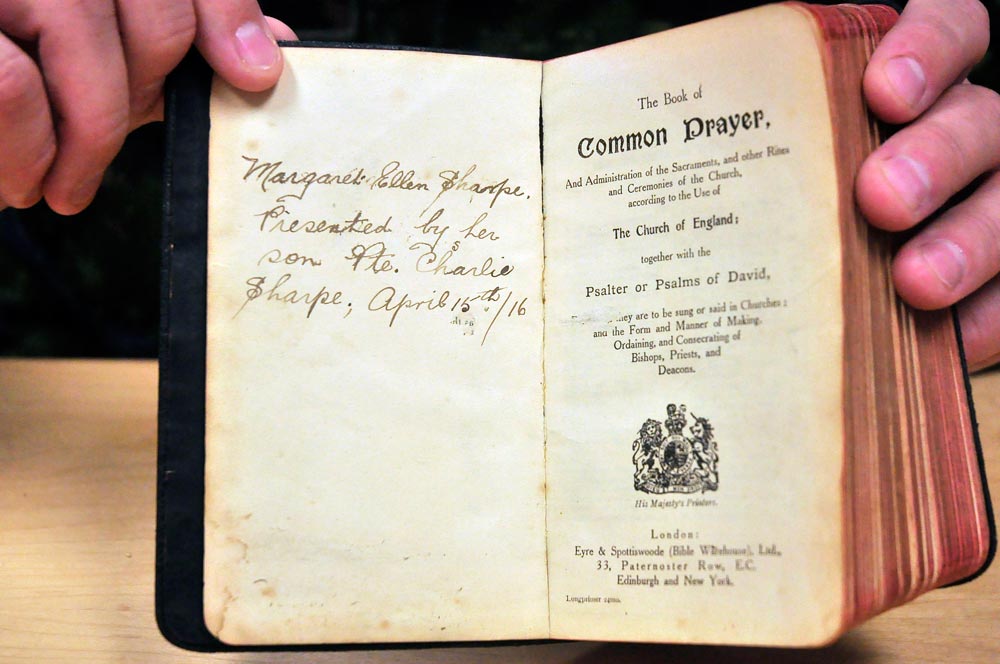

LCol Reg Sharpe was able to obtain his great-grandfather’s Dead Man’s Penny, a bible presented to his great-grandmother before Pte Charles Sharp left Newfoundland for Belgium to serve with the BEF during the Great War. He also has Pte Sharp’s medal for his service. Photos Jules Xavier/Shilo Stag