Jules Xavier

Shilo Stag

On the 106 anniversary of the Battle of Vimy Ridge this past April, Kendra Minary was thinking about her great-great-uncle Pte Cecil Minary.

She spent the COVID-19 pandemic researching her relative, who was Killed In Action (KIA) east of Arras, France on Aug. 28, 1918. She had the luxury of letters he wrote home to tell her about his experiences overseas. The original letters are housed at the Wawanesa Museum, which opens in July.

Standing five-foot-eight, Pte Minary enlisted in Winnipeg on Nov. 30, 1915, leaving his bachelorhood on the farm to fight in the Great War. Born on July 6, 1895 in Nesbitt, he joined the Little Black Devils 144th Battalion. Kendra learned he nearly never made it overseas.

“While in early training at Camp Hughes he very nearly died from pneumonia,” she said, acknowledging in the days before antibiotics it took him more than seven months to recover

He was sent to hospital in Winnipeg, from Camp Hughes, on Dec. 15, 1915. He returned to his unit on March 20, 1916. He then returned to hospital with heart problems, according to his attestation paperwork, this time he was hospitalized from May 9 to 16, and again from May 26 to Aug. 29.

Despite a delay in training in the trenches of Camp Hughes, Pte Minary was exposed to what he would expect to see when Canada led the charge on entrenched Germans on Vimy Ridge, France, in April 1917. The training area west of Carberry replicated what the battlefield in France resembled thanks to aerial photographs taken by the RAF.

Pte Minary left Halifax, NS, on Sept. 18, 1916 aboard a troop-laden SS Olympic, arriving in Liverpool, England, on Sept. 25. He began further training after being Taken On Strength (TOS) on Jan. 12, 1917 in Seaford.

“He had been picked in a draft of 30 men to join the 52nd Battalion,” said Kendra. “The 52nd was still a reserve unit in April at the time of the Vimy Ridge battle, but Cecil’s letters tell of seeing action shortly after.

“It would appear his unit was continually in and out of the battle lines until at least August 1918.

“In Cecil’s letters he spoke of some close brushes with death and of friends being killed or wounded. But Cecil seemed to have had a charmed life because in the same action, he was only shot through the heel of his boot.”

Pte Minary finally arrived in France on Feb. 2, 1917, TOS seven days later. He saw duty finally on April 12.

“There is little in his letters to suggest of the horrors and hardships we now know these men endured,” offered Kendra. “In fact, he would appear to do his best to make light of it all.”

Pte Minary’s letters to his family back in Canada revealed that as of October 1917 he was in charge of his Lewis machine gun crew. The previous soldier in charge was wounded, and had to undergo a serious operation to remove a piece of shrapnel which struck his temple and it was unknown when or if he would return to France.

What else did her great-great-uncle’s letters tell of his Great War experience?

“Cecil stated he carried no rifle, just a revolver and the Lewis machine gun and he was the man who did all the shooting when the Germans were in sight.”

With the 100-day push on with allied troops pushing the Germans back from territory they held for much of the four-year war, tragedy struck the 52nd battalion in late summer 1918.

“Unfortunately, on Aug. 28, he and his crew of six other men were hit by an artillery shell near Bois Du Vert, France. Six of the seven men, including Cecil, were killed.”

Earning $20 per month during the war, Pte Minary was 23 when he was KIA.

He is buried in the Vis-En-Artois British Cemetery in Pas de Calais, France — Plot VII, Row 6, Grave 16.

The COVID-19 pandemic has afforded Kendra the time research her family history, including that of her great-great-uncle Cecil.

“Cecil’s story is very fascinating,” she said. “I would love to find ancestors of the man who survived the artillery shell hit that killed my great-great-uncle to see if they have any of his stories or letters.”

Pte Minary’s military skills did not go unnoticed on the battlefield in France. He was awarded a Good Conduct Badge in the field on Nov. 30, 1917.

His great-grandfather also served, but Kendra said she knows little about his time in the Army.

“My dad said he never talked about it. It was probably too hard after losing his brother,” she said.

During the pandemic Kendra has spent time typing out the more than 60 letters she has from a war that ended 75 days after Pte Minary died.

While Pte Minary volunteered to go overseas, his five-foot-six, 133-pound younger brother William was drafted at age 21.

Born on Oct. 25, 1896, the young farmer, also a bachelor like his big brother, had his medical in Brandon on Nov. 19, 1917, and signed his military paperwork on June 5, 1918.

With casualties mounting in France and Belgium, where the CEF concentrated its soldiers, William Minary was called to serve, not volunteer, under the Military Service Act 1917.

He was sent to Winnipeg on Aug. 7 and joined No. 10 Engineers and Railway Construction Corps. By Aug. 15 he was Struck Off Strength (SOS) and received $16.50 in pay. He would see no military action, and was officially discharged on Jan. 9, 1919.

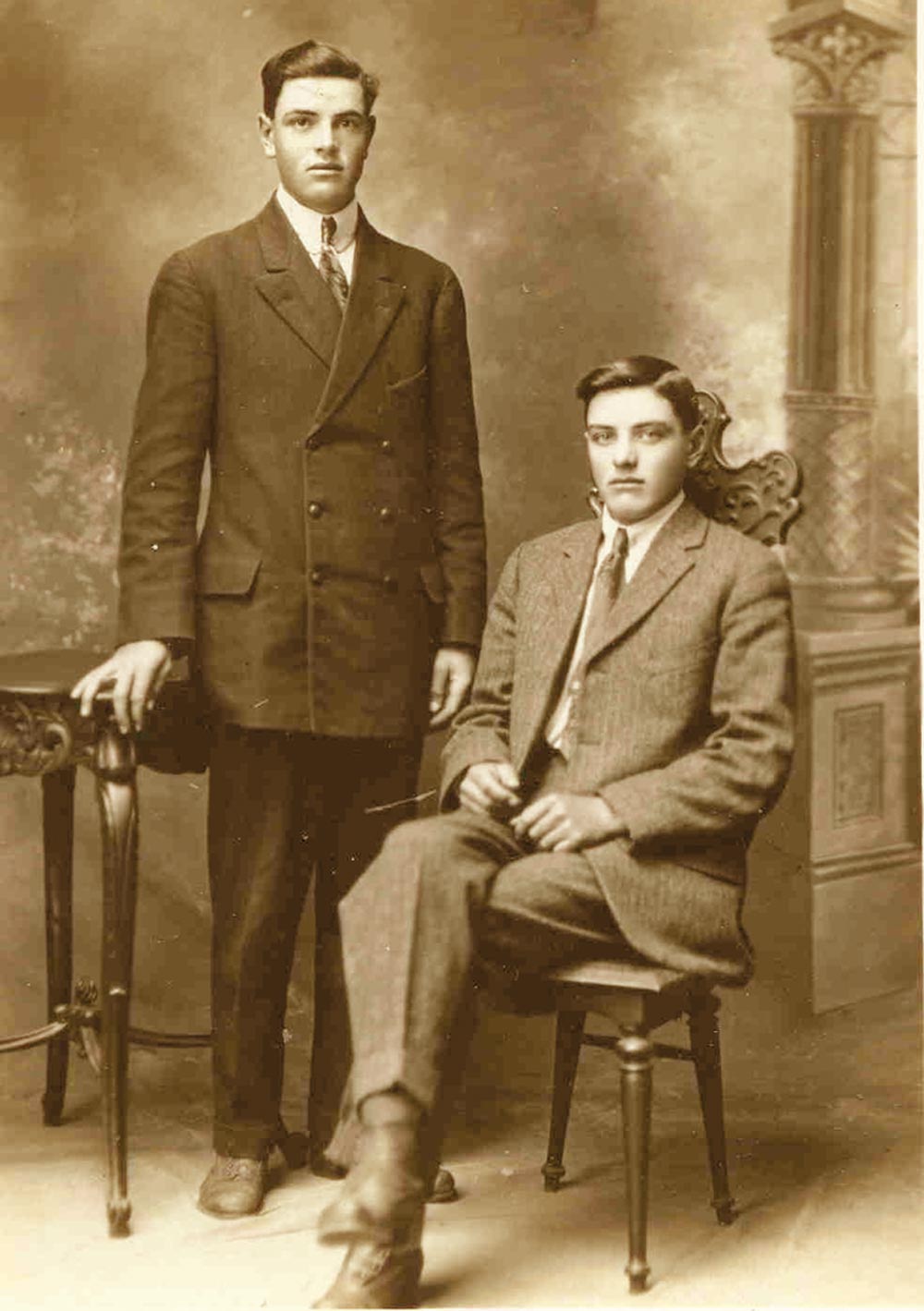

After training at Camp Hughes, and surviving near-death medical issues in Manitoba, Pte Cecil Minary went overseas and saw action shortly after the Battle of Vimy Ridge had started in April 1917. He was in charge of a machine gun crew (below). He was KIA on Aug. 28, 1918 and is buried in France. While overseas he posed for studio photos solo, or with fellow CEF volunteers. He managed to have a photo taken with brother Bruce prior to going overseas. Kendra Minary one day would like to visit his gravesite overseas. The house Pte Minary grew up still stands on the former family farm in Nesbitt, however, it has not been lived in and is likely ready for a wrecking ball to bring it and the history in it down, laments Kendra. Photos supplied by Kendra Minary/Souris