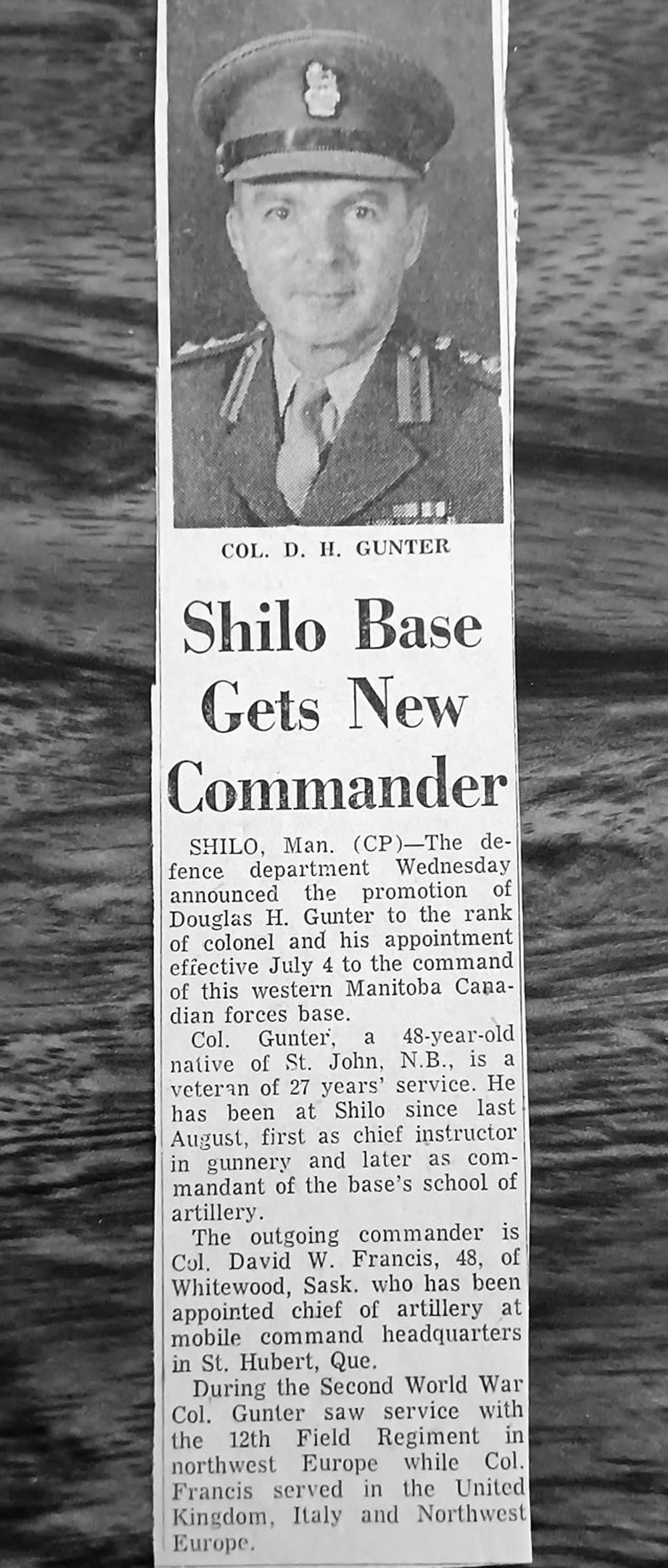

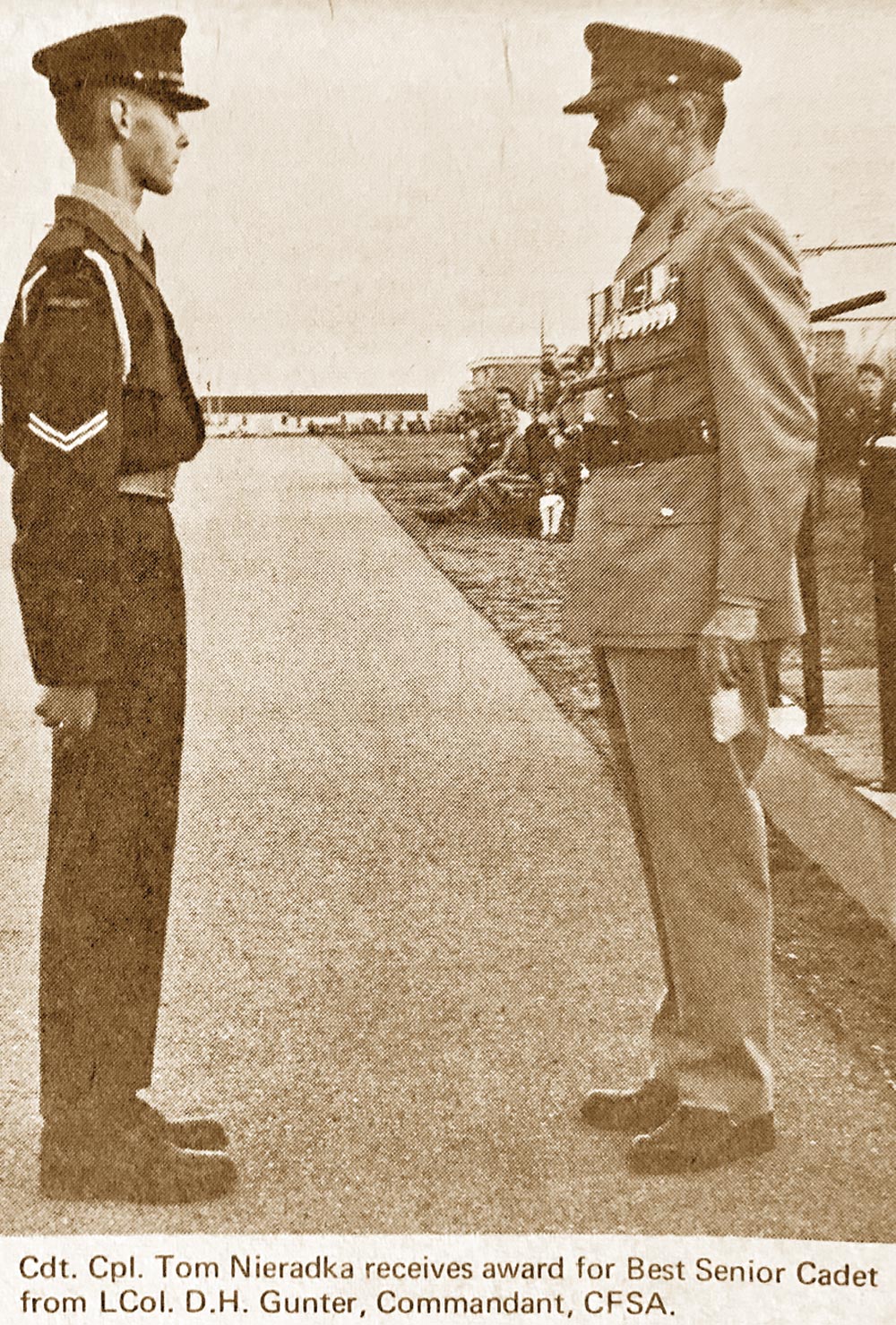

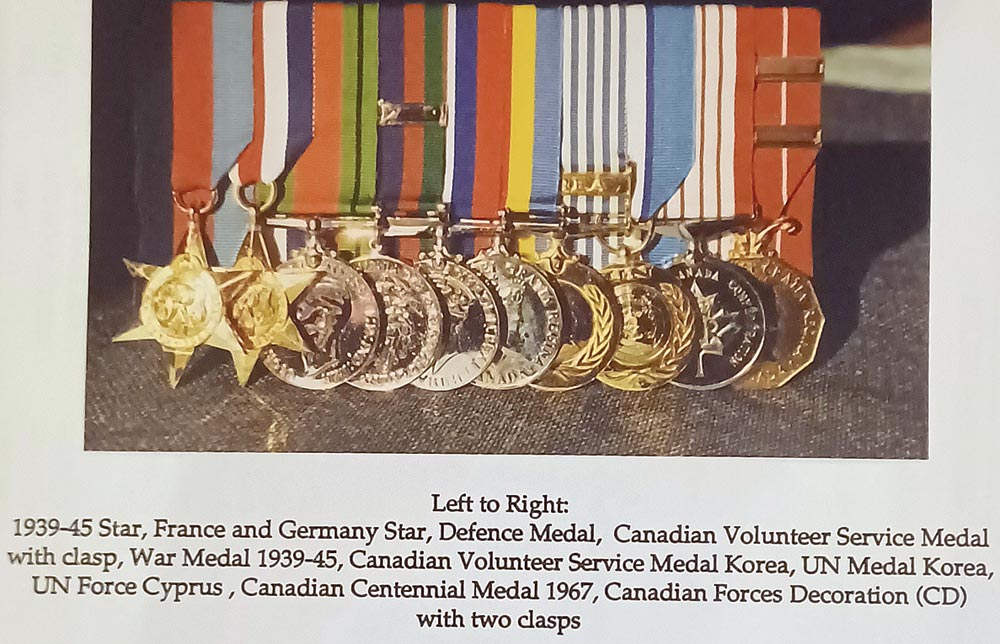

Editor’s note: Then Capt Douglas H. Gunter wrote a diary during his early days posted to Camp Shilo, arriving here in the fall of 1946. He would have a few postings to this Base, including a stint as BComd from 1969 to 1970, with wife Jo and their two children Richard and Anne. Retiring after 32 years with the Royal Regiment of Canadian Artillery, he died on March 4, 2005 in his 84th year. A graduate from the University of New Brunswick in 1942, he then saw action in the Second World War during operations in Northwest Europe (12 Field Regiment RCA), followed by Korea and peacekeeping duties in Cyprus. He held various command and staff appointments including Commander of A Battery, RCHA; Brigade Major 3CIBG; Commandment Canadian School of Artillery as well as CFB SHILO BComd. He was Director of Land Requirements and Director of Artillery on retirement in 1974. He then became executive director of the Canadian Figure Skating Association serving in various capacities for 17 years.

Col Douglas Gunter

Stag Special

Jo (Josephine) and I left Fredericton (NB) by train in high spirits for the wild west in early October 1946. Having been told that Shilo is “just west of Winnipeg” we were pleased to get off the train in that city after almost three days of bumping and lurching. When we got into a taxi at Winnipeg Station and asked to be taken to Shilo, the driver cooling informed us that would be another 125 miles west. We hastily dismounted with our bags and waited for the next train which dropped us off at the Shilo CNR whistle stop at 2 a.m. Someone gave us a lift into camp, where we registered at the “Hostess Hut.” The night clerk seemed friendly considering it was now 3:30 a.m., until I tried to accompany my wife to the room. “No men allowed” I was informed icily. I finally found shelter in the officers’ mess as dawn was breaking.

On reporting for duty after a short catnap, I was informed that I would be starting a course that afternoon, meanwhile there was time to take over our married quarters. Jo and I had been assigned a section of HP5 — a wartime H hut which had been used as CWAC quarters, with pictures of movie stars still pinned to the walls. The central area of the hut had running water with a common ablution area, toilets and showers (no bathtubs). The wings had been roughly partitioned off into six family areas. The Gunter residence had three-quarter length partitions forming four rooms: a long narrow space which became the living room, the room closest to the running water (although we never had any) we decided would be the kitchen. The other two were bedroom, dogs and storage. Heating was from a central steam plant (if too hot open windows). Monthly rental for this “emergency quarter” was $17.10 per month including light and heat.

After showing Jo and I, of course, had to run off to my course but not without reassuring her that I would be home for supper. Meanwhile, she could settle in. Fortunately, a kind neighbour lent her a hot plate, which we were able to borrow for a part of each meal hour until Percy White of the Hudson’s Bay Company sent us our very own stove from Winnipeg. A modicum of initial furniture came from the unit QM stores. Except for a daily milk delivery, initially all groceries had to come from the general store in the village of Douglas, 10 times away. Later the Arty Shop was set up in camp to provide a modest selection of groceries. Also the “Blue Goose” bus made shopping runs to Brandon, some 25 miles away.

When you live in the middle of nowhere transportation becomes a major problem, and during that period right after the war it was almost impossible to buy a car. Automobile plants were just changing over from war production and demand for new cars was at a peak. I tried in New Brunswick and Ontario without success. There were long waiting lists and, if a car was available, most dealers charged pricey “key money” over and above the list price for the privilege of buying the car. However, I lucked out at Western Motors in Brandon who apparently just before my visit had decided that they wanted to place a car in Shilo. They sold me a new black Chevrolet coupe for the list price of $1,414. We were very proud of that car with the possible exception of one cold night when we drove to a hockey game in Brandon. Leaving the rink at midnight, everyone in the parking lot seemed to be cranking their cars while mine leapt into action at a touch to the starter. I drove away, nose in the air, until we got about five miles out of town and the engine stopped in mid-flight. Nothing would respond, including the heater. I got out into the black night and kicked the tires. It was very cold and we had no heavy clothing. I started to think of al those stories about prairie folk freezing to death in their own backyards. Fortunately, another car came along, driven by a friend, Suds Sutherland, who had been to the same hockey game. He pushed us the remaining 20 miles to Shilo. The temperature was reported that night as -47 degrees F, cold enough to freeze my gas line at full speed, even though there was anti-freeze in it. From then on we always carried emergency clothing in the car during the prairie winter. We drove that car for three years and sold it after 30,000 miles for $300 more than we paid for it. I falsely concluded that cars were a good investment. Never again.

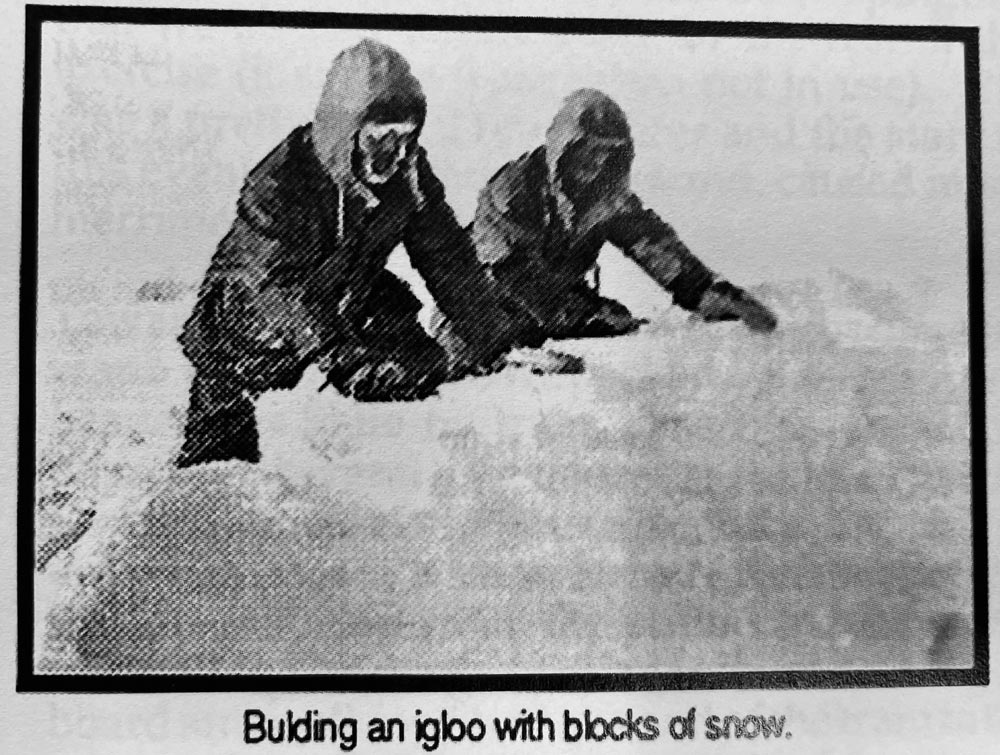

ARCTIC TRIALS

That first winter, in January 1947, I went to Fort Churchill on Hudson’s Bay with a group from Shilo to test winter clothing and the performance of artillery weapons under Arctic conditions. Our trials were preceded by an Arctic conditions. Our trials were preceded by an Arctic indoctrination course — how to live and move in the far north, including navigation (virtually impossible) and the construction of snow caves and snow houses (depends on the snow). Our greatest enthusiasm was devoted to a trial on the benefits, if any, of using issue rum in the north. The fun froze but we managed to ladle out the slush by spoon. We all enjoyed it but the medical report was adverse — just because a few extremities got frozen!

We spent three months in the Churchill area and the longer we stayed the more out clothing looked like that of the natives. We decided that fringe on cuffs of sleeves and pant legs, as the Eskimos wore, provided dead air space for additional warmth, and that their caribou hide with the fur inside made a lighter, warmer parka than our synthetic materials — but don’t bring it into a warm area where it will soon stink from limited tanning.

Generally, our guns worked well in the cold. We learned to keep any exterior gears, normally greased, absolutely clean and dry. Otherwise, they became blocked by blowing snow turned to ice. Digging spade holes to stop rearward movement on firing was impossible in the frozen tundra. We found that flowing the holes with beehive explosive charges was the answer. It was also necessary to put a block of wood or branches (not easy to find in the Arctic) in the hole behind the spade to prevent damage on recoil.

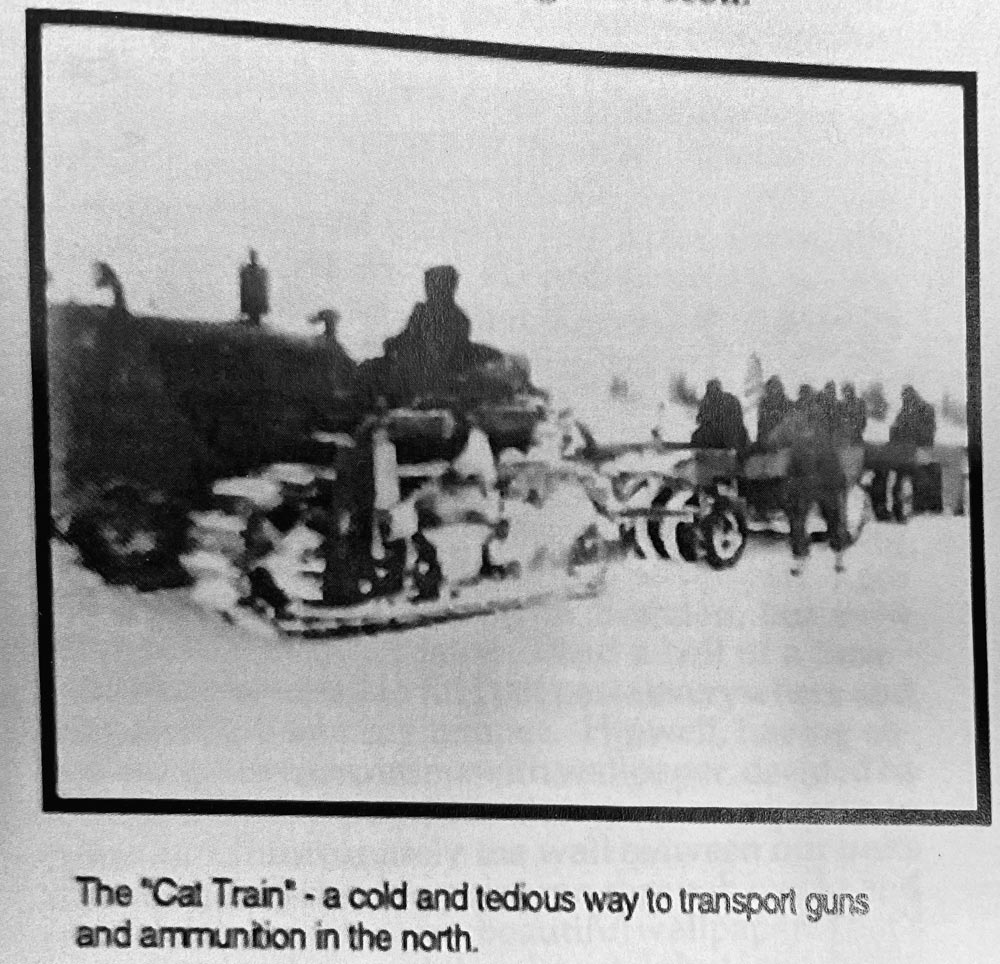

Movement was slow and difficult, towing our guns and ammunition by tractor (cat train) and navigation next to impossible. But perhaps the main difficulty was that people got clod in the north and inevitably spent most of their energy just trying to keep alive (the war would have to wait). We found that the best way to keep warm at night whether in an igloo, snow cave or tent, was to slide into your sleeping bag stark naked. After you recovered from the first shock all was well once your body heat warmed the inside of the bag. However, the cold snow below tended to stimulate kidney action and we were frequently faced with the frightening prospect of going outside for a leak in the middle of the bitterly cold Arctic night.

During our survival course the instructor’s helpful advice was to locate an empty tin or other container within reach on going to bed, for use inside the sleeping bag during the night, if necessary. I remember one occasion when I was sharing a tent with my friend, Earnest Hopewell, and others. Apparently I had cursed the Army, the Arctic and the -40 F night at at 3 a.m. as I struggled to dress and exit the tent to relieve myself. Then I heard Hipwell’s voice from inside the tent asking why I hadn’t acquired a tin as instructed, like he had? There was a long pause, then a sudden scream. Apparently Hip had picked up his tin at the kitchen and failed to notice that the bottom had been perforated prior to heating its contents. The result was a soaked sleeping bag that we all had to live with for the rest of the exercise (it simply froze when not in use). Hip was a pretty formal type officer ad the story of this event, which soon got around, caused much merriment among the troops.

Toward the end of March the weather became too warm for our trials, so we packed up our guns and headed for Shilo by train. The trip took 2 ½ days, with several long pauses as the train waited for large herds of caribou to clear the tracks. The only real railway station en route was at The Pas, but the train seemed to stop at every native settlement along the way, with the Indians coming on board and walking from one end of the train to the other to inspect the passengers with friendly curiosity. I suppose we were the only show in town. It also gave us a chance to check meat supplies stashed high in trees beside family shacks with their dog teams tied below. Truly basic living.

We were pleased to rejoin our family and get back to the relative luxuries of Shilo, with inside plumbing and steam heat. Actually it wasn’t that luxurious — as I have said, when we first moved in we had been able to get some furniture from QM Stores until we could get our own. But while we were in Churchill the policy changed and the QM picked up their furniture. As a result both Hip and I found our wives sitting on blankets on the floor when we got back. Neither Jo nor Hip’s wife Monna could buy furniture in our absence, as the husband’s signature was needed to use Rehab Credit, a World War II benefit, our only asset then. This was obviously a first priority and we soon gathered the necessary minimum of furniture and appliances from Brandon and Winnipeg. I bought one appliance from Jake Beer who was going to England on course — a kitchen sink.

As I have reported, we had no running water in our unit, but I was confident that I could convince the camp engineer (now my good friend) to run water pipes in. I installed the sink in the kitchen but we continued to fetch pails of water from an outside tap to do the dishes. Every now and then I absentmindedly poured water down the sink — and it tumbled out on the floor! I never did manage to get our very own water put in.

We also got into interior decorating. We painted most of the place but decided to give the living room special treatment, using wallpaper. I got the paper and materials in Brandon, but even with unpatterned paper I had a hell of a time — nothing seemed to fit, I got paste everywhere and frequently lost my temper. Hipwell, having observed my frustration with wallpaper, decided he would spray paint his living room adjacent to mine. Unfortunately the wall between our units was so thin that his paint ran through cracks and down the inside of my beautiful wallpaper. That’s really togetherness! It took a while but I eventually saw the funny side.

On first going to Shilo I was assigned to C Battery but soon after return from Fort Churchill I was promoted Captain and appointed Adjutant 1RCHA. At that time the unit consisted of one field battery, one anti-tank battery and a medium battery — a mixed bag. As adjutant I worked directly for the CO, Lt Col Webb, my war-time commanding officer, whom I both admired and liked. There were lots of organizational and training problems with the unit, but the main preoccupation of everyone in these early post-war days was to make this temporary war-time camp in the middle of nowhere liveable for families and to plan for a permanent town with all the necessary amenities.

First priority was just to keep alive during the long, cold winter. To this end officers and men took shifts on “fire picket.” This involved shovelling coal and stocking fires all night long throughout the camp. We organized our own grocery/clothing store — the Arty Shop. We hired a staff, but had to do our own stock taking, accounting, etc. We soon had our own daily milk delivery (Gunner White was our milk man). We dug a hole in the ground, lined it with sand bags and tarpaulins and called it the village swimming pool. Unfortunately because of winter freezing it collapsed in a couple of years.

On Wednesday afternoon sports, most officers were detailed to work on the Shilo golf course. This gradually emerged with sand greens, fairways replete with many gopher holes that swallowed our balls and poison ivy everywhere. We eventually developed nine holes. Of course there are now eighteen, ever grass greens!

Col Webb was very involved with all these projects, in addition to keeping the heat on Ottawa for a permanent camp site. This meant routinely working seven days a week. He and his dog Muggs used to call for me on Sunday mornings. He would rap on my living room window with his stick on the way to the office. The message was clear that I was expected there, too.

Mugs was a Springer Spaniel. He was the Colonel’s constant companion — on inspections, on parade and in the office where he lay beside the Colonel’s desk and added to the general confusion during orderly room cases. RSM Seed shouted orders as he marched in the accused and witnesses whose steel-clad jack boots made an ungodly noise as they marched and stamped on the flimsy floor, entering Roly and Muggs’ inner sanctum. By this time Muggs, thoroughly aroused, would bark in terror at all this shouting and stamping and the CO would shout at the dog. It didn’t add to the dignity of the legal system, but everyone for mile around sure knew that a summary trial was being held.

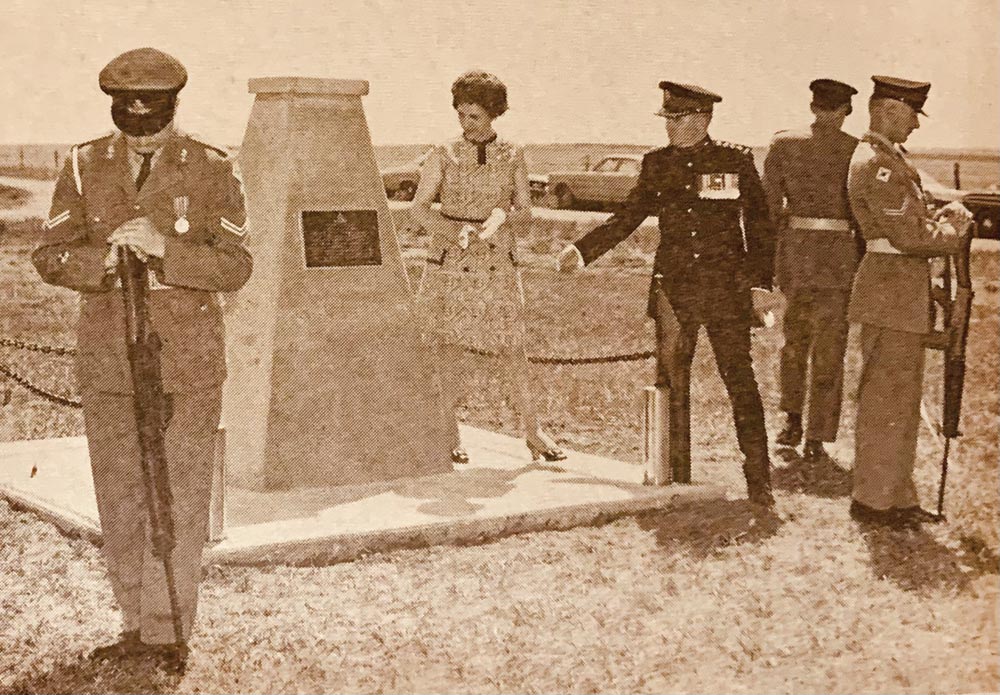

An array of photos from the Shilo Stag during Col Douglas Gunter’s time as BComd, July 1969 to July 1970. Also a few photos lifted from his diary when he first arrived at Camp Shilo as a young RCHA officer, and during his training trip in the Arctic.