Stag Special

On July 5, 1916, the Department of Defence and Militia authorized the formation of No. 2 Construction Battalion.

It was the largest Black unit in Canadian history. Its members continued the proud tradition of service to king and country that went back to the American Revolution and continued through the War of 1812 and the Rebellions of 1837–38 to the start of the First World War.

But there were many obstacles: Black soldiers and communities faced racism both at home and overseas, despite their commitment to the war effort.

In August 1914, more than 10,000 men across Canada rushed to their local recruiting centre to enlist for service in the First World War. Many Black men tried to enlist as well, but were rejected; some were told this was a white man’s war, while others were told their services were not required.

By the end of 1915, at least 200 Black volunteers had been rejected. This reflected the racism in Canada at the time. Many white men told recruiting officers and Battalion Commanding Officers (CO) they refused to serve with Black men.

These rejections were unacceptable to the leaders of Black communities across Canada. They wrote to Militia headquarters and the governor-general to request that Black Canadians be allowed to enlist. They also questioned why they were being rejected.

At the same time, senior Militia officials across Canada were also questioning Militia headquarters in Ottawa, asking how Black men could be allowed to enlist. They too faced pressure from Black leaders as well as the refusal of many white men to serve with Black soldiers.

An all-Black infantry battalion was not an option. There were not enough Black men in Canada to man such a Battalion and provide reinforcements in the face of heavy casualty rates at the front. Further, the British War Office refused to allow any Black units into combat on the Western Front — they feared that Black infantry units might use their training and experience against British authorities in the colonies.

In April 1916, the chief of the general staff at Militia headquarters found a solution. He proposed a Black labour Battalion be formed, labour being in very short supply and critical to support campaigns. The British approved the idea in May.

No. 2 Construction Battalion was authorized on July 5, 1916 under the command of LCol Daniel Sutherland, a well-known railroad contractor from River John, Nova Scotia.

Its headquarters were initially based in Pictou, Nova Scotia, but moved to Truro in September. A detachment operated in Windsor, Ont., from September 1916 to March 1917 for soldiers recruited in Ontario and western Canada.

Recruiting began in the Maritimes on July 19, and in Quebec and points west on Aug. 30. The Battalion was one of only a few units which was allowed to recruit across the country.

By the end of December 1916, it had 575 soldiers. As with other battalions, many of these were released as medically unfit before the battalion sailed. The numbers enlisted were good, but not enough for a Battalion.

On Dec. 22, 1916, the Battalion was told it should prepare for service overseas. Its services were urgently needed. A large recruiting push began, to get the battalion up to strength.

It was interrupted when 250 men from Truro were sent to New Brunswick in late January 1917 to remove railway tracks immediately required for military railways in Belgium and France.

On March 28, 1917, No. 2 Construction Battalion sailed from Halifax on the SS Southland. They arrived in Liverpool on April 7. The Battalion sailed with 19 officers and 595 men, far short of the 1,049 officers and men required for a Battalion.

Of the officers, only one, Rev William Andrew White, was Black; there were seven non-Black soldiers among the troops. Among these were the two highest NCO positions in the unit: the Regimental Sergeant Major (RSM) and the Regimental Quartermaster Sergeant (RQS).

In England, the War Office would not allow the Battalion to go to France with so few men. The solution was to reform the Battalion as a labour company of 500 officers and men, renamed No. 2 Canadian Construction Company. The rest of the Battalion remained in England to serve as reinforcements.

The Canadian Forestry Corps urgently needed labour to support its forestry operations in the Jura Mountains in southeast France. No. 2 Canadian Construction Company arrived there early on May 21, 1917 and immediately began operations.

No. 2 Construction Company performed a large number of supporting tasks. These included improving the existing logging roads in the La Joux Forest and helping build a logging railway. The company also operated and maintained the system that provided water to all the camps, as well as the electrical system when it came online.

In addition, they transported the finished lumber products to the railway station, where they loaded them into railway cars. In performing these tasks, the lumberjacks of the Forestry Corps companies were freed to cut and mill trees. No. 2 Construction Company was also involved in all phases of the lumber process, helping saw down trees and move and mill the logs.

Did you know? Lumber was essential for the war effort. It was used for revetting the sides of trenches and for duckboards for the bottom of trenches or across muddy terrain. It was also used for artillery gun platforms, railway ties, ammunition boxes, accommodation huts and bridges.

The work of No. 2 Construction Company allowed the mills to produce more than twice as much lumber as mills that did not have this support.

In November 1917, a group of 50 men from the company were sent to No. 37 Company at Péronne, France; there they helped build a road used to move supplies to the front. They then continued to support lumber operations.

Another group of 180 men was sent to northwest France, near Alençon to support the companies of No. 1 District, Canadian Forestry Corps. They were sent there in the mistaken belief that Black men of No. 2 Construction Company from the Caribbean and the United States could not handle the cold of the Jura Mountains.

The soldiers of No. 2 Construction Battalion who remained in England were soon assigned to reserve infantry battalions where they conducted infantry training and menial labour while awaiting the call to serve at La Joux.

In total, 67 became reinforcements for the company at La Joux; one group of 50 arrived in April and another of 17 in June. Most of the remainder went on to serve with Canadian Forestry Corps companies in Belgium, France and the United Kingdom.

With the Armistice on Nov. 11, 1918, the Forestry Corps was no longer required. To get a head start on repatriating soldiers to Canada before the planned departure of combat troops, Canadian Forestry Corps companies were returned to England.

The first men of the CFC and No. 2 Construction Company began their return on Dec. 2, 1918.

A large group of soldiers from No. 2 Construction Battalion arrived in Kinmel Park in Wales in late December to await transport to Canada. On Jan. 7, 1919, some of the men were attacked by white soldiers after the Battalion’s (Black) sergeant tried to arrest a white soldier for insolence.

The white soldiers refused to accept the rank and authority of the Black sergeant despite all of them being in the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF).

In the effort to quickly return soldiers to Canada, members of the Battalion were put onto the first available ships. These included the RMS Aquitania, RMS Empress of Britain and RMS Olympic.

When these troop ships arrived in Halifax in January 1919, the soldiers from outside Nova Scotia were placed on trains to be taken back to their province of enlistment.

The majority of the battalion’s soldiers returned on these three ships and were discharged by the end of February. The Battalion was disbanded on Sept. 15, 1920 as Militia Headquarters dissolved the CEF.

The men of No. 2 Construction Battalion showed the dedication of Black communities across Canada towards their country. It was the largest Black unit in the history of Canada and played an essential role in the lumber operations of the Canadian Forestry Corps in Jura and Alençon.

Facing rejection and racism, Black men successfully pushed for recognition and an active role in the war. This success demonstrated that Black communities across the country had a political voice.

In July 1920, a commemorative plaque recognizing the battalion’s casualties was unveiled at the provincial legislature in Toronto; it was rededicated in September 1926.

In 1920, Capt M. Stuart Hunt compiled Nova Scotia’s Part in the Great War, which summarizes the activities of every unit raised in Nova Scotia during the First World War. It includes a chapter on No. 2 Construction Battalion.

However, No. 2 Construction Battalion was soon forgotten, as it was not a combat unit. The Battalion remained almost unknown until Calvin Ruck began his research into the Battalion in the 1980s. The Government of Canada recognized the creation of the Battalion as a national historic event in 1992, the same year Ruck was appointed to the Canadian Senate.

A granite monument commemorating No. 2 Construction Battalion was erected at Pictou, Nova Scotia, in 1993 and was declared a national historic site.

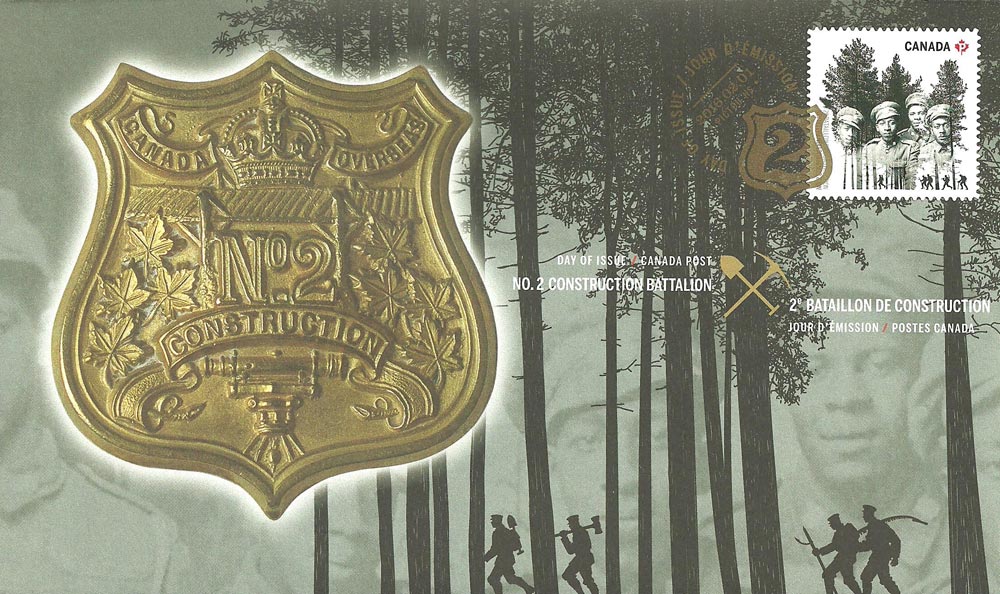

Canada Post issued a first day cover and a commemorative stamp for Black History Month in February 2016 recognizing the Battalion.

On July 9, 2022, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau apologized on behalf of the federal government to the descendants of No. 2 Construction Battalion for the systemic racism experienced by members of the Battalion.

In the ceremony at Truro, Nova Scotia, he also announced the Royal Canadian Mint would honour the Battalion with a commemorative coin for Black History Month this past February.

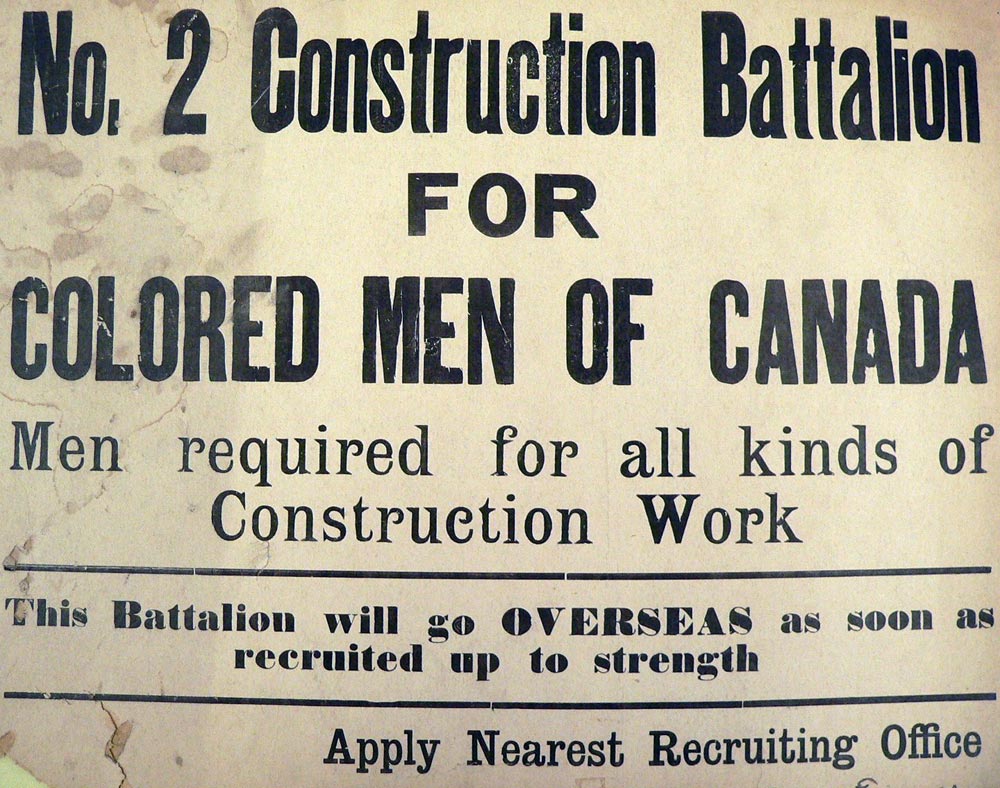

Recruitment poster for the No. 2 Construction Battalion courtesy Esther Clark Wright Archives at Acadia University

The officers of No. 2 Construction Battalion are pictured in France. The CO LCol Daniel Sutherland, is seated on the left of the front row, while the unit chaplain, Honourary Capt William Andrew White, is front row centre. Photo courtesy LCol DH Sutherland Collection, River John, Nova Scotia

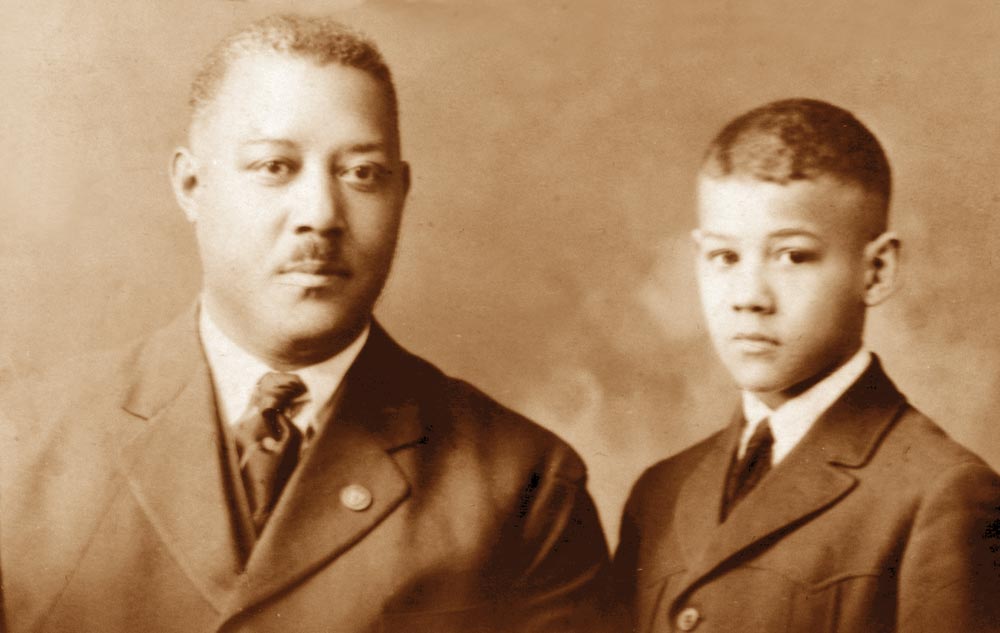

Ginger Lamoureux’s great-grandfather Cpl Damascus Virgil with son Owen. Photo supplied Lamoureux family archives

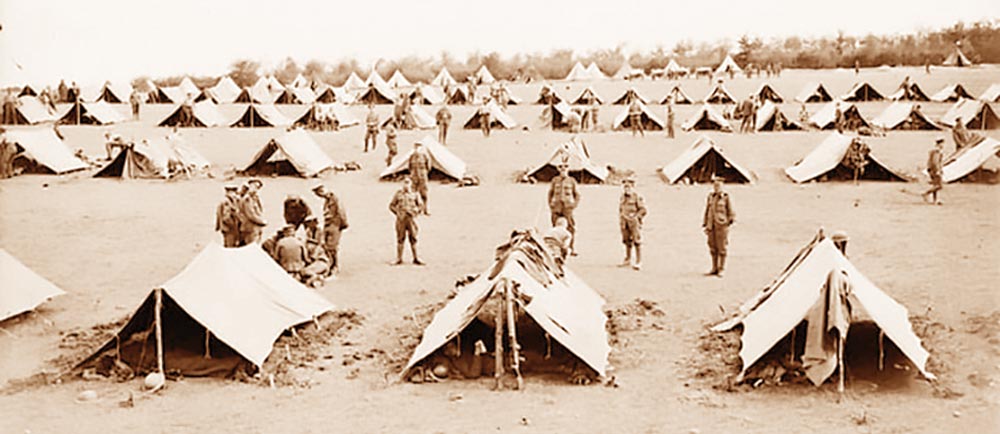

No. 2 Construction Battalion members in Nova Scotia before leaving for France in the spring of 1917.

Ginger Lamoureux discovered negatives featuring her grandfather Owen and great-grandfather Cpl Damascus Virgil. Photo Jules Xavier/Shilo Stag

Cpl Damascus Virgil is buried in Port Arthur, now Thunder Bay Ont. following his death in 1947.

Soldiers enjoy a meal while sitting in a trench built by No. 2 Construction Battalion using wood from the Canadian Forestry Corps.

During training, soldiers with No. 2 Construction Battalion lived in open-air tents.